When people talk about growth, they usually assume the discussion is about getting more people to your product. When we really dig into growth problems, we often see that enough people are actually coming to the products. The real growth problems start when people land… and leave. They don’t stick. This is an onboarding problem, and it’s often the biggest weakness for startups. It can also take the longest to make meaningful improvements when compared to other parts of the growth funnel.

In my role as Growth Advisor-in-Residence at Greylock, I talk to startups in the portfolio about getting new users to stick around. Through many failed experiments and long conversations poring over data and research, I have learned some fundamental truths about onboarding. I hope this can function as a guide for anyone tackling this problem at their company.

What is Successful Onboarding?

Before you can fix your onboarding efforts, you need to define what successful onboarding is to you. What does it mean to have someone habitually using your product? Only then can you measure how successful you are at onboarding them. To do so, you need to answer two questions:

- What is your frequency target? (How often should we expect the user to receive value?)

- What is your key action? (The action signifies the user is receiving enough value to remain engaged)

To benchmark frequency, look at offline analogs. At Grubhub, we determined how often people ordered delivery by calling restaurants. The answer was once or twice a month, so we used a “once a month” as a benchmark for normal frequency for Grubhub. At Pinterest, the analog was a little harder to determine, but using Pinterest was most like browsing a magazine, which people read weekly or monthly. So we started with monthly, and now they look at weekly metrics.

Identifying the key action can be easy or hard — it depends on your business. At Grubhub, it was pretty easy to determine. You only received value if you ordered food, so we looked at if you placed a second order. At Pinterest, this was a little harder to determine. People derive value from Pinterest in different ways, from browsing lots of images to saving images to clicking through to the source of content. Eventually, we settled on saving (pinning an image to your board), because, while people can get value from browsing or clicking through on something, we weren’t sure if it was satisfying. You only save things if you like them.

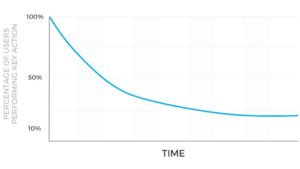

Once you know your key action and your frequency target, you have to track that target over time. You should be able to draw a line of all users who sign up during a specific period, and measure if they do the key action within the frequency target after signup. For products with product/market fit, the line flattens as a percentage of the users complete the key action every period:

If the line flattens rather quickly, your successful activation metric is people who are still doing [key action] at [set interval] at [this period after signup]. So, for Pinterest, that was weekly savers four weeks after signup. If your cohort takes a longer time to flatten, you measure a leading indicator. At Grubhub, the leading indicator was a second order within thirty days of first order.

How should you research onboarding?

You can break down cohort curve above into two sections. The part above where the curve flattens are people who “churn”, — or did not receive enough value to make the product a habit. The people below where the curve flattens have been successfully onboarded.

To research onboarding, talk to both groups of people to get their thoughts. I like to do a mix of surveys, phone calls, and qualitative research using the product. I usually start with phone calls to see what I can learn from churners and activators. Our partner Josh Elman talks about best practices to speaking with churners, or bouncebacks. If I am able to glean themes from those conversations, I can survey the broader group of churners and activators to quantify the reasons for success and failure to see which are most common. (Sidenote: You’ll need to incentivize both groups to share their thoughts with you. For those that didn’t successfully activate, give them something of value for their time, like an Amazon gift card or money. For those that did, you may be able to give them something free in your product.)

But it is not enough to just talk to people who already have activated or churned. You also want to watch the process as it’s happening to understand it deeper. In this case, at Pinterest, we brought in users and watched them sign up for the product and go through the initial experience. When we needed to learn about this internationally, we flew out to Brazil, France, Germany and other countries to watch people try to sign up for the product there. This was the most illuminating part of the research, because you see the struggle or success in real time and can probe it with questions. Seeing the friction of international users first hand allowed us to understand it deeper and focus our product efforts on removing that friction.

The principles of successful onboarding

#1: Get to product value as fast as possible — but not faster

A lot of companies have a “cold start problem” — that is, they start the user in an empty state where the product doesn’t work until the user does something. This frequently leaves users confused as to what to do. If we know a successful onboarding experience leads to the key action adopted at the target frequency, we can focus on best practices to maximize the number of people who reach that point.

The first principle we learned at Pinterest is that we should get people to the core product as fast as possible — but not faster. What that means is that you should only ask the user for the minimum amount of information you need to get them to the valuable experience. Grubhub needs to know your address. Pinterest needs to know what topics you care about so they can show you a full feed of ideas.

You should also reinforce this value outside the product. When we first started sending emails to new users at Pinterest, we sent them education on the features of Pinterest. When Trevor Pels took a deeper look at this area, he changed the emails to deliver on the value we promised in the first experience, instead of telling users what we thought was important about the product. This shift increased activation rates. And once the core value is reinforced, you can actually introduce more friction to deepen the value created. When web signups clicked on this content on their mobile devices, we asked them to get the app, and because they were now confident in the value, they did get the app. Conversely, sending an email asking users to get the app alone led to more unsubscribes than app downloads.

Many people will use this principle as a way to refute any attempts to add extra steps into the signup or onboarding process. This can be a mistake. If you make it clear to the user why you are asking them for a piece of information and why it will be valuable to them, you can actually increase activation rate because it increases confidence in the value to be delivered, and more actual value is delivered later on.

Principle #2: Remove all friction that distracts the user from experiencing product value

Retention is driven by a maniacal focus on the core product experience. That is more likely to mean reducing friction in the product than adding features to it. New users are not like existing users. They are trying to understand the basics of how to use a product and what to do next. You have built features for existing users that already understand the basics and now want more value. New users not only don’t need those yet; including them makes it harder to understand the basics. So, a key element of successful onboarding is removing everything but the basics of the product until those basics are understood. At Pinterest, this meant removing descriptions underneath Pins as well as who Pinned the item, because the core product value had to do with finding images you liked, and removing descriptions and social attribution allowed news users to see more images in the feed.

Principle #3: Don’t be afraid to educate contextually

There’s a quote popular in Silicon Valley that says if your design requires education, it’s a bad design. It sounds smart, but its actually dangerous. Product education frequently helps users understand how to get value out of a product and create long term engagement. While you should always be striving for a design that doesn’t need explanation, you should not be afraid to educate if it helps in this way.

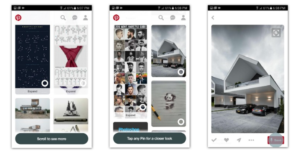

There are right and wrong ways to educate users. The wrong way: show five or six screens when users open the app to explain how to do everything — or even worse, show a video. This is generally not very effective. The right way: contextually explain to the user what they could do next on the current screen. At Pinterest, when people landed on the home feed for the first time, we told them they could scroll to see more content. When they stopped, we told them they could click on content for a closer look. When they clicked on a piece of content, we told them they could save it or click through to the source of the content. All of it was only surfaced when it was contextually relevant.

Onboarding is both the most difficult and ultimately most rewarding part of the funnel to improve to increase a company’s growth. And it’s where most companies fall short. By focusing on your onboarding, you can delight users more often and be more confident exposing your product to more people. For more advice on onboarding, please read Scott Belsky’s excellent article on the first mile of product.

Currently listening to Easy Pieces by Latedeuster.