When founders of startups start to hire employees to work on various parts of the business, it tends to be uneasy for both the founder and the employee early on. The founder may have done that job in some capacity before they hired for it, but they are not an expert. The incoming employee may bring more expertise, but they don’t know the business yet. The founder is going to have a lot of opinions as is the employee, and they won’t necessarily match. In this essay, I’ll talk about how to think about balancing founder intuition vs. team expertise, and how that changes over time. I find that this same balance is true for customers vs. founders when they start businesses too, so we’ll cover that as well.

Generally, the biggest mistake founders can make when starting to hire a team is defer too many decisions too quickly to new employees. This is most painful with new executives, but can also be damaging when hiring new individual contributors. Founders frequently convince themselves that this new person they hired is an expert on this topic, and they should defer to them. The opposite actually tends to be true. The founders are experts on the business. And incoming employees should defer to them until they are confident they have become more of an expert on a certain aspect of the business.

The opposite mistake tends to happen later on as the business grows. The founders have now staffed the company with a lot of great talent who have had time to learn the business, have impact, build processes, know customers really well, etc. Meanwhile, the founders are scaling a bigger business and getting further away from the details. Founder intuition becomes less reliable because the founder(s)’ advantage of having spent more time on the problem goes away. Their thoughts become perhaps dated. And they won’t really know it. This degradation of founder intuition also happens at different times for different parts of the business.

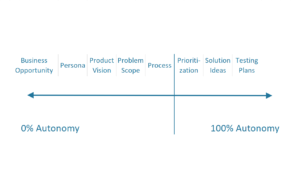

Great founders start to back away from relying on founder intuition when they see the expertise developing on the team, or are proven wrong in a meaningful way by the team that makes them start to question their often blind faith in their own judgment. Moving forward, founders have to calibrate how their intuition stacks up against team expertise on every topic of the business to know how much to intervene vs. let the team drive. Think of this as a simple graph.

It’s incredibly hard to accurately graph where the founders and team are on this graphic for every topic within the company, and when they cross. Normally, founders tend to navigate this based on factors like personal interest, what areas of the company they perceive to be doing well or not, etc. Having worked with lots of founders myself as a leader, advisor, investor, or board member, I default to founders needing to operate differently at different stages. On a bunch of different axes, I have mapped how I think companies optimally behave as they grow (changes in italics).

| Phase 1: Starting | Phase 2: Scaling | Phase 3: Expanding |

| Founder makes decisions | Founder starts to delegate decisions | Founder empowers team completely |

| Speed > Precision | Speed with some precision | Precision > Speed |

| Generalist > Specialist | Specialist = Generalist | Specialist > Generalist |

| Done > Perfect | Done > Perfect | Done Perfect Trade Off |

| Focus > Breadth | Focus > Breadth | Breadth Focus Tradeoff |

| Execution > Strategy | Execution > Strategy | Strategy = Execution |

| Hungry > Seasoned | Hungry > Seasoned | Seasoned > Hungry |

| Cheap > Robust | Cheap Robust Trade Off | Robust > Cheap |

| Teamwork > Process | Some process | Process First |

| Doers > Managers | Doers with some doer-managers | Managers + Specialists |

Obviously, this table can be a bit crude, and understanding when the company is shifting between phases is not always apparent to everyone inside the company. But it provides a default guide on when to delegate and empower teams as a company grows. I find that just asking the question of what phase the company is in builds good awareness on how one might want to be operating at the moment.

If you are a startup employee or leader, you have to respect founder intuition greatly. The company would not have gotten to the point you could have even been hired had that intuition not served the company well. But when you’ve really spent the time to understand the business and you or your team can start to have better judgment than the founder, it’s important to signal that confidence and get alignment on the operating model shifting. It will not be an easy conversation, but worthwhile to have.

What can you gain from such a conversation? First, you make the above graph visible to the founder in a way they may not be aware. Second, you can calibrate where each of you think you are on this graph. If the founder believes their intuition still serves the business better on a topic than the expertise you have built, then you can have a conversation about what would signal those two lines crossing to change how decisions are made in that area? Keep in mind, in some cases, that answer may be that there will never be a signal that changes how much control the founder wants to exert in an area. Companies are not democracies, and founders have the right to run the company any way they want. If they want to drive decisions on what tech stack the company uses or which segments are interesting, they will. If you don’t like it, you should join another company. But most founders want to do what is best for the company, and giving them the signal on where it’s valuable for them to lean in vs. that potentially being unhelpful is worth figuring out.

On the flip side, if the founder is putting decisions on you or your team where the founder would be better fit to make the calls themselves, tell them! There is no shame in admitting you’re not yet equipped to make the calls and empowering the founder to make more direct decisions for a while. This is not an admittance of incompetence. It’s driving clarity on decision-making rights that are optimal for the business. If you’re still asking the founder to make those same calls a year later though, expect them to think you aren’t developing the expertise you should be.

What is ironic about founders and employees facing this split between intuition from expertise is both have to do that same analysis with the company’s customers. When startups are small, most founders and employees tend to think the customer knows best. This may be experienced by changing the product based on customer feedback, allowing customers to experiment with different ways to use the product that help them become successful, etc. But as a company scales, it starts to see every way customers use a product, and what works best. For a marketplace like Airbnb, it might be seeing that hosts that provide toiletries get higher ratings, or for Eventbrite it might be seeing that emailing past attendees of an event a certain time before the next event maximizes their chances of buying another ticket. Then, the company’s job switches from observing what customers are doing and adopting them to teaching customers what best practices the company is aware of that will make them more successful.

So, in summary, founder intuition is extremely valuable, and new employees and leaders should learn to leverage that vs. ignore it because they’ve seen things before. But founder intuition does ebb over time in most areas as founders scale up the company, and of course, teams get a lot smarter as they spend time on deep company problems. This also happens with your customers over time. Having a dialog about where teams are in this journey is important to helping startups scale, clearing a path for teams to have maximum impact, and for leveraging founders’ scarce time in the areas that are most highly leveraged.

Currently listening to my 2022 playlist.