This blog post was adapted from a presentation I did recently. Hence, slides. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

I receive a lot of questions about growth teams. Naturally, there is a lot of confusion. Is this marketing being re-branded? Who does this team report to? What is the goal of it? What do they actually work on? When do I start a growth team for my business?

The purpose of growth is to scale the usage of a product that has product-market fit. You do this by building a playbook on how to scale the usage of a product. A playbook can also be called a growth model or a loop.

The first question you should ask before asking about growth is if you have product-market fit?

The traditional definition above is qualitative, and if you’re like me, you like to have data to answer questions. The best way to get that data for most businesses is to measure retention.

The best way to identify the key action is to find a metric that means the user must have received value from your product. The best way to understand the frequency on which you should measure that metric is how often people solved this problem before your product existed. Let’s look at some examples from my career.

For Pinterest, a Pinner receives value if we showed them something cool related to their interests. The best way to determine if the Pinner thought something we showed them was cool is that they saved it.

For Grubhub, this was even easier to determine. People only receive value if they order food, and when we surveyed people, they ordered food once or twice a month (except for New York).

Once you have a key metric and a designated frequency, you can graph a retention curve or a cohort curve. If it flattens out, that means some people are finding continual value in the product. But that is not enough.

Brian Balfour has a great post on this, which he calls product-channel fit.

If you’ve been around startups for a while, you might remember this tweet from Paul Graham. It talked about the fastest growing startup Y Combinator has ever funded. It is a graph of revenue growth from $0 to $350,000 per month in just 12 months.

If you’ve been around startups for a while, you might remember this tweet from Paul Graham. It talked about the fastest growing startup Y Combinator has ever funded. It is a graph of revenue growth from $0 to $350,000 per month in just 12 months.

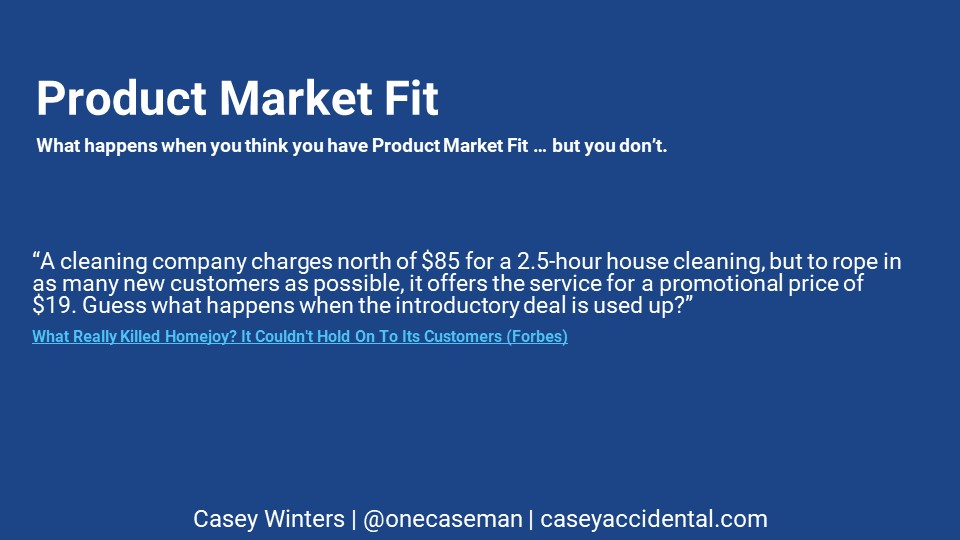

The startup was Homejoy, an on demand cleaning service. Investors liked this graph, so they gave the company $38 million to expand.

20 months later Homejoy shut down. From a post-mortem of the company, I highlight the following quote.

If you discounted to get to product-market fit, you didn’t get to product-market fit. Product-market fit is not revenue growth, it’s not growth in users, it’s not being #1 in the App Store. Product-market fit is retention that allows for sustained growth.

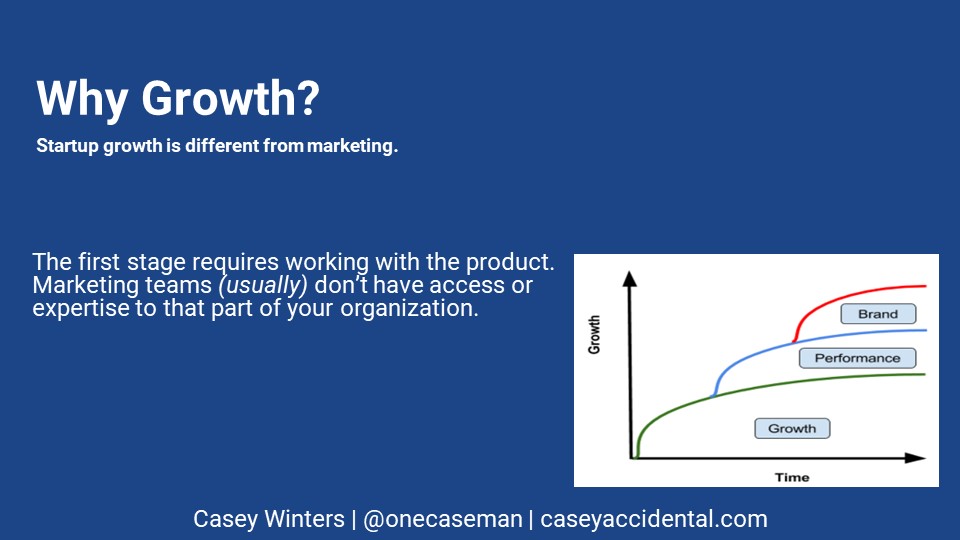

So, I though product teams were in charge of creating a product people loved, and marketing teams were in charge of getting people to try the product. What changed?

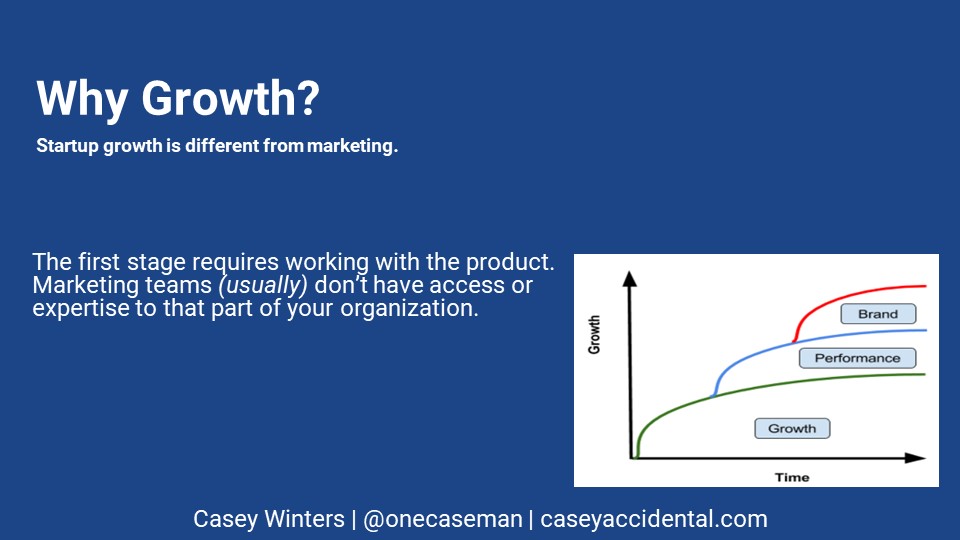

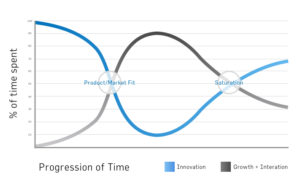

What changed is an acknowledgement of what actually drives startup growth. There are three main levers. Phase I is simultaneously the most important and the least understood. In Phase I, you change the product to increase its growth rate. Some changes include improving onboarding, helping the product acquire more customers through activities like virality or SEO, incresing the conversion rate, et al.

These initiatives are “free” in that they don’t require an advertising budget. Their cost is the opportunity cost of a product team’s time. They are measurable in that you can create an experiment and understand the exact impact of the change. They are also scalable in that if you make a change that, say, improves your conversion rate, and it has a certain amount of impact, it likely will have that same impact tomorrow, weeks from now, and potentially even years from now.

The other two phases are what we traditionally think of as marketing. Performance marketing initiatives, like buying ads on Facebook or Google, are also measurable and scalable, but scale with an advertising budget. Brand marketing usually requires an even larger ad budget, and is harder to measure or scale. The time frame over which brand marketing works takes years, and can be hard to confirm. If you do create a PR campaign or a TV ad that seems to work on a more immediate time frame, it can be hard to scale. that is because brand marketing always requires new stories to keep people’s attention.

This is why marketing can’t be in charge of all growth initiatives. They don’t have access or capability to the most important ones. They might know they need to improve the site’s conversion rate or get more traffic from referrals, but they don’t have access to the product roadmap to get them prioritized appropriately, and if they do get engineering and design help, they don’t have the expertise in working with them to build the best solutions.

Perhaps what’s more important to understand in the difference between marketing and growth is how the traditional marketing funnel changes with startups. Above is the traditional marketing. This model is based on the old school model of product development before the internet in spending a lot of money to make people want things.

Startups by definition should be making things people already want. When you do that, you can invert the funnel and focus on people that already want the product or people that are already using it. This is more effective on a small (or no) budget.

When you translate that into tactics, you see how product-driven growth initiatives dominate the top of the list of priorities. It does not mean you won’t work on performance marketing or brand marketing, but that they usually become important later on in a product lifecycle as an accelerant to an already sustainably growing company.

So I spent a lot of time explaining why growth is different from marketing. How is different from product?

Growth teams don’t create value. They make sure people experience the value that’s already been created.

The most common examples to start a growth team to address are:

- improving the logged out experience (for conversion or SEO)

- sending better emails and/or notifications

- increasing referrals or virality

- improving onboarding

SEO and onboarding are harder places to start because their iteration cycles are much longer than the other areas.

Growth teams don’t start by finding mythical VP’s of Growth to come in and solve all of your problems. They are usually started by existing employees at a company (or founders) that really understand the company and what’s preventing it from growing faster. They report to their dedicated functions, but sit together to focus on problem solving.

To find out which area you work on after you have the team, you have to analyze the data. For example, at Pinterest, they originally wanted me and my team to work on SEO. What we saw was that while there was a lot of opportunity to get more traffic via SEO, a bigger issue was the conversion rate from that traffic. So we decided to work on conversion instead.

Then we had to figure out what to work on. Jean, an engineer on the team, had recently run an experiment that gave us a key insight. So, we said, we could use this same modal when people clicked on Pins. Clicking on a Pin could show enough interest in Pinterest for you to want to sign up.

The other thing people did when they liked what they saw scroll to see more. So, we decided to try stopping them where we stopped the Google crawler, and asking them to sign up then.

It took Jean two days of work to launch this experiment, and it resulted in a much bigger impact than expected.

So that’s an example of finding a conversion issue in you data, and putting together a really scrappy experiment to try to improve it. What else can growth teams work on? Here are some examples from my time at Pinterest, and some best practices we’ve learned.

Usually, the biggest area a growth team focuses on improving is retention. That’s right; growth teams are not just about acquisition. Retention comes from a maniacal focus on improving the core product, which I define as core product, not growth, work. Where growth comes in is reducing friction to experience that core product. Simplifying how the current product works usually has much more impact than adding new features. New features complicate the product, making it harder for new people to understand.

So how do you simplify the core product? Well, you have to have data to understand what people do, and pair it with qualitative research to understand why they do it. We spent countless hours at Pinterest putting laptops in front of non-users watching them sign up for the product to figure out why people didn’t activate.

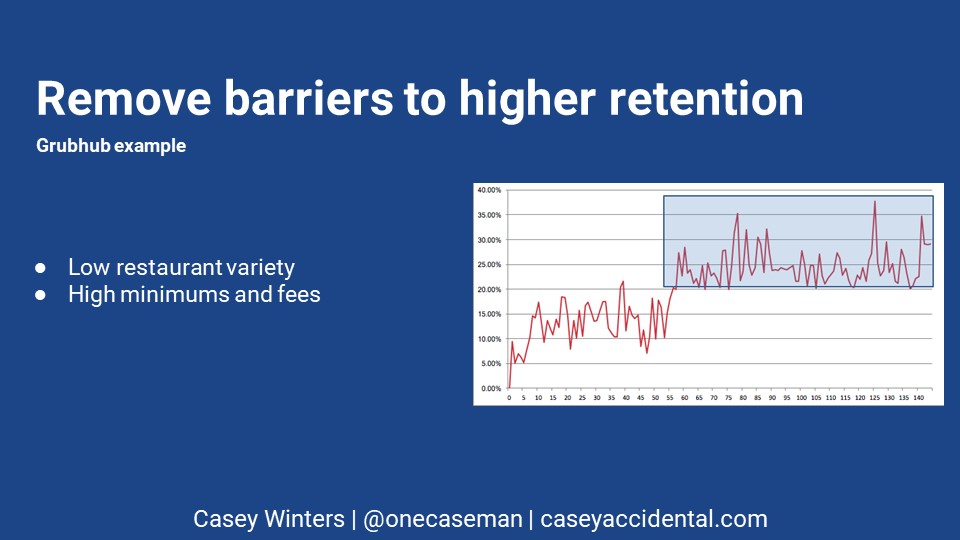

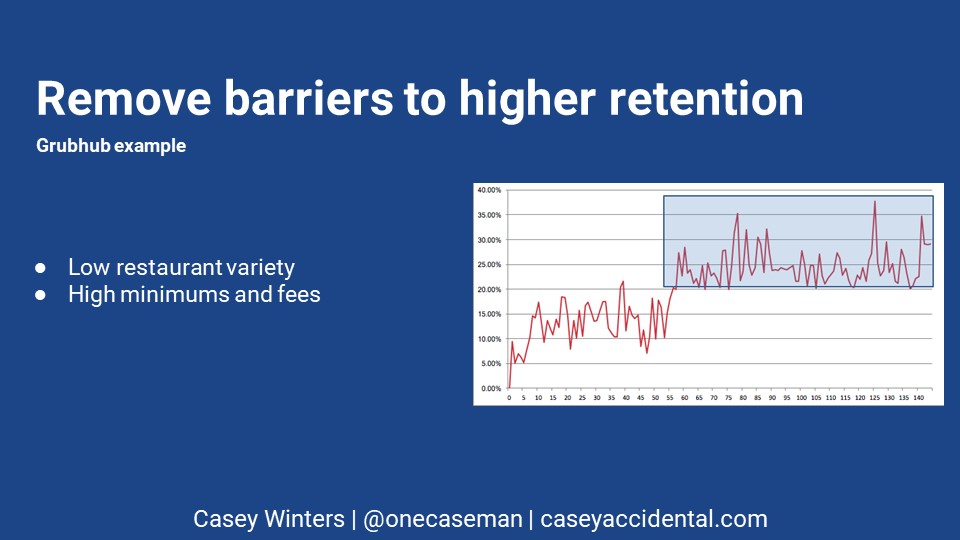

At Grubhub, data pointed out that Grubhub was an S curve when it came to both conversion and retention. This graph is a (now very old) graph of conversion rate in Boston based on how many restaurants Grubhub returned when you searched your address. After 55 results, conversion rate essentially doubled for new and returning users.

Qualitative research gave us different insights. When we asked users why they didn’t use Grubhub more often, they would say, “it’s expensive.” We thought that was weird, because Grubhub wasn’t charging them anything. What they meant is that delivery was expensive due to minimums and delivery fees. So, we went back to our restaurants, convinced a few to try lowering their minimums and fees to see if increased volume could make up for lower margin. When it did, we creates case studies to help convince other restaurants.

At Pinterest, we simplified the signup and onboarding flow. What used to be a flow that required five steps was now three with one of them pre-filled and the other two optional. What we did do was introduce friction that we knew made it more likely a Pinner would find content they care about. This was asking them which topics interested them before showing them a feed of content.

We also realized that the more content people see, the more likely they will find something they like, which will lead to retention. So, we removed content around Pins that was non-critical, like who Pinned it to what board and how they described it. All of these increased activation rates.

We also contextually educated people on what to do next when they were onboarding. There is a common saying that if you need to add education to your design, it’s a bad design. It’s pithy and sounds smart, but it’s actually dangerous. My response is that a design with education is better than a design that doesn’t educate.

Search engine optimization has been a really great lever for organic growth for every company I’ve worked on in my career. It’s not for every business though. People need to already be searching for what you do. That alone isn’t enough though. You need to be an authority on the subject, which Google determines by relevant external links to your domain and your content. You also need to be relevant to what was just searched.

We worked on improving both of these at Grubhub. When Grubhub launched new market, by definition we weren’t locally relevant yet. So we would go to local blogs and press outlets and tell them we were launching there, and that we wanted to give their readers $10 off their first order. All they had to do was link to a page where the discount would auto-apply. After a while, that page would have enough local links so that even though the promotional discount was over, it would still rank #1 for the local delivery terms e.g. “san francisco food delivery”.

For relevance, Grubhub knew which restaurants delivered where, their menu data, and reviews from real people. So we aggregated them into landing pages for every locale + cuisine combination e.g. ‘nob hill chinese delivery”.

We applied the same landing page strategy at Pinterest. While Pinners had created boards on their favorite topics, it was one person’s opinion on what was relevant for a topic. Pinterest has repin data globally for every topic, so we knew what the best Pins were across the Pinterest community. So we created topic pages with the best Pins, and they performed better than individual boards on search engines and with search engine users.

We also worked a lot on emails and notifications on the Pinterest growth team. Emails are a key driver of retention. They won’t solve your retention problem, but they will certainly help if you do them right. At every company I have been at, people hated email and didn’t want to send them to their customers. When they finally did, they saw lifts. You are not your customer. You get more email than they do. Emails help them if they’re connected to the core value of why they use your product. Emails are not helpful if they’re pushing a marketing message.

At Pinterest, I made this mistake. I set up campaigns with emails that explained all of the things Pinterest could do. People don’t care about what Pinterest can do. They care about seeing cool content related to their interests. We needed to stop sending email like a marketer, and start sending email like a personal assistant. So we replaced those emails with popular content in topics of interest for each Pinner, and our retention increased.

Then, we built a system around it. Each Pinner likes different content, at different times, and different amount of it. So we learned for each Pinner what content they liked, when they liked to receive emails and notifications (based on when they opened them), and how much they liked to receive based on testing different volumes and seeing open rate impacts.

If you’re testing emails and notifications, you can test manually first, then automate and personalize. What I have learned at Pinterest and Grubhub is what seems to be worth testing. At Pinterest, one engineer tested 4,500 different subject lines, resulting in hundreds of thousands of additional weekly active users. Around the same time, we spent three months redesigning all of our emails, and it had no impact on usage.

A common issue I see with growth and marketing teams is they think that emails and notifications can only have positive impact. This is not true. You have to measure the lift in usage vs. the unsubscribes (and the impact of an unsubscribe) and app deletions. Those will impact usage, and you need to know how.

—

Growth teams have a clear purpose, and that purpose makes sense only if you have first found product-market fit. Once you have that, you will find traditional product and marketing lacking in their ability to help scale usage of your product. That’s where growth teams come in. Growth teams use data and qualitative research to help understand the frictions that prevent more people from finding the value in your product. That can mean acquisition, but it can also mean reducing friction in the core product, working on conversion or onboarding, or finding ways to remind existing users about the value you’re creating. If you have questions about growth teams, don’t hesitate to reach out to cwinters@greylock.com.

This presentation was made in conjunction with @omarseyal, who is awesome.

Currently listening to Everybody Works by Jay Som.