I receive many questions about how to build marketing at technology organizations. New entrepreneurs hear terms like growth, user acquisition, and positioning, and don’t know where to start. This should be a handy guide on how marketing looks for a healthy technology organization and why. To start, I’ll re-iterate the definition and explanation of the definition of marketing from my The Incredible Unbundling of Marketing post to understand how we cover everything that is traditionally considered a marketing activity.

Marketing is the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.

Source.

Since that’s a mouthful, marketers tend to shorthand with a series of P’s (four to seven depending on who you ask). For products, those are product (the creating part of the definition), price (the exchanging part of the definition), promotion (the communicating part of the definition), place (the delivering part of the definition), positioning (the value part of the definition), people (the people who do the activity), and packaging (another part of the communicating piece of the definition). For services, those are product, price, promotion, place, people, process, and physical evidence.

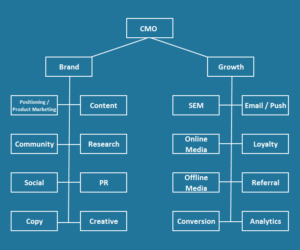

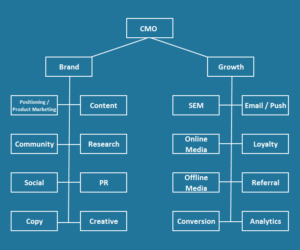

At technology companies, the product piece is typically carved out as a separate team, and various approaches exist for carving up the rest of the P’s. The most typical is to have a CMO in charge of marketing, and two VP’s that split two types of marketing that tend to require different skills (change that to VP’s and directors if you like).

Brand Marketing

Brand marketing typically includes the strategic and soft skills of marketing. These include the positioning, the target market, packaging, and physical evidence. Positioning primarily transitions to what the brand represents for its target, which is why the group is traditionally called Brand Marketing. They also tend to include the promotional elements that are less quantifiable: PR, content, social, community management, events, campaign building, etc. To be successful in positioning and identifying target markets, market research tends to be in this group.

Growth Marketing

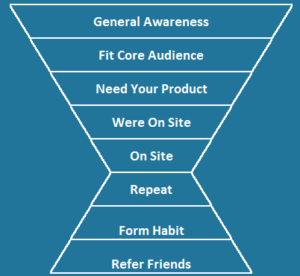

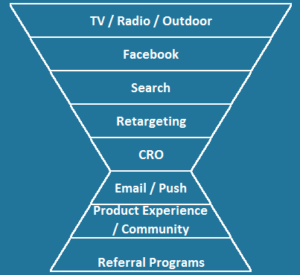

Also known as performance, internet, digital, or online marketing due to its heavy reliance on those areas (sometimes also acquisition and retention marketing), growth marketing typically includes price, process and the parts of promotion that are quantifiable. These include SEO, email marketing, loyalty programs, landing pages, paid acquisition in almost all forms (not just online), referral programs, direct mail, and analytics about marketing and product performance.

How does Growth Marketing work with Brand Marketing?

These two organizations need to work hand in hand, Brand marketing determines who the product is for, and Growth Marketing is primarily responsible for getting people to start and to continue using the product. Growth Marketing determines the best ways to find the target market and reach them, and they work with Brand Marketing to receive appropriate creative that reflects the positioning. Growth Marketing should see branding as increasing the conversion rate on all of their activities. Brand Marketing should see Growth Marketing as the distribution engine for their message.

What about the product?

As we saw in the marketing definition above, product is one of the key P’s that does not seem to be owned by marketing. Also, what is typical in many technology companies is that some of the best opportunities to get people to start using the product come from the product itself (SEO, virality, and landing pages are the main ones), and marketers typically lack the authority as well as the technical skills to make these changes. Product and engineering organizations own these areas. So, what has become common is creating cross-functional teams where growth marketers, engineers, and product managers work together to help growth the product. Depending on which distribution methods work best for the product, the product manager and growth marketer can be indistinguishable or the same role.

Early on in a technology company, there is so much opportunity with product driven growth, that just product managers and engineers work on growth marketing. Growth Marketing tends to emerge as product managers become too busy with core product features, when expertise becomes more of a necessity, and when channels that are less product driven (paid acquisition, email,etc.) become more important. Paid acquisition is usually only tried once a lifetime value can be established, so that growth marketers can be sure to spend significantly less than that to acquire a customer.

How should the Growth cross-functional team work with Growth Marketing?

Growth Marketing needs to become a key stakeholder in the cross-functional growth team in key areas. I have spoken of cross-functional teams before, and the key elements. As we grow, we need to expand a three to four person group to include a growth marketing lead. Not every sub team needs a lead to start. You should never hire to fill org charts, only to add additional value. It should only be where they add value, and the cross-functional team adds value to them. In many of these areas, the product manager is also the growth marketing expert in the area, so the position would be redundant. The first area where Growth Marketing should fit typically would be on paid acquisition or email marketing, depending on the company. This person would get support from the team on the infrastructure to make paid acquisition or email successful (tracking, landing pages, etc.), and this person would bring in knowledge on success from these channels that can be applied to organic channels.

How does Brand Marketing work with a Core Product team?

Brand Marketing should be an early voice in the core product development process helping to mold who the new products is for and how it is positioned. Once development is kicked off, typically the Product Marketer becomes a project manager designed to maximize launch impact of the feature and ongoing adoption, coordinating between the rest of the Brand Marketing team (PR, social, content, events, campaigns,etc.) and the Core Product team. It’s important a Product Marketer has short and long term metrics for adoption.

What does the org chart look like typically?