As I advise startups on growth, one of the most common questions I receive is “should we be working on SEO?”. At this point, I tend to remind them of the three phases of scaling startup marketing or show them Andrew Chen’s great post on the few ways to scale user growth. In today’s mobile-first landscape, with the limited scale of the App Store/Google Play, the answer is actually a bit more nuanced. So I created a guideline on how to answer this question for any startup.

Step 1: Keyword Research

The first question to answer when thinking about SEO for your business is “what should my business show up for?”, which really is asking the question, “what is my business about?”. Unlike branding, where the point is to synthesize that answer into as few clear words as possible, keyword research is about generating as many answers to that question as possible. These will be your potential keywords. I like to use the framework: who, what, when, where, how to answer this question. Let’s take the example of GrubHub:

Who: GrubHub, restaurant names we represent

What: food, delivery, menus, pizza, thai, indian, chinese

When: breakfast, lunch, dinner, late night

Where: every city, neighborhood, zip code, college covered

How: online ordering, mobile app, iphone app, android app

Take these words, combine them all into new keyword combinations in Excel e.g. “late night pizza delivery berkeley”, and check to see how much search volume they have. To do that, use the Google Adwords Keyword Planner. Click “Get search volume for a list of keywords”. Take the keywords from the exercise above and paste them in. Click “Get search volume”. Click on Keyword Ideas tab. You can also do this process again to find new keywords by clicking “Search for new keyword and ad group ideas” at the beginning.

You can now see how much search volume is closely related to your business. Search volume determines how much your prioritize SEO for your business. Now, there is no hard and fast rule for how much search volume there needs to be for you to get excited about it as an opportunity. It depends on purchase size, how much you want to grow, etc. Generally, I recommend taking all of those keyword’s search volume, assuming you can get a very small percentage of it to your site e.g. 1%, and seeing if that would make an impact on your business.

Now that you have an idea of the search volume for your business, you need to know how competitive that real estate is. Fortunately, Google estimates how competitive they think each keyword is next to the search volume estimate. It lacks the granularity I’d like, but it’s a good starting point. What I do in addition to looking at this gauge is do some spot searches and see what the results look like. Here, I’m looking for two things:

1) Are the results primarily businesses you would consider competitors or blogs?

2) Are the pages that are showing up well optimized for the keywords you searched or not? Are they dedicated landing pages or home pages? (I’ll go into more detail on how to measure this a little later in this post)

Step 2: Picking an SEO Strategy

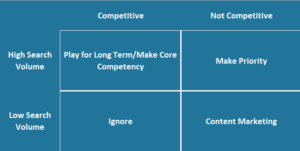

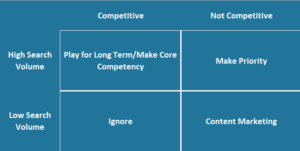

Now, you should have an answer to two questions:

1) Do my keywords have a lot of search volume?

2) Are those keywords competitive or not?

This creates four scenarios:

High Search Volume/Low Competition: Make Priority

This is a rare opportunity, and you can build a great business just off of SEO here. You should make SEO a priority and one of your primary growth strategies.

High search volume/High Competition: Play for Long Term/Make Core Competency

This means the ROI is there with SEO in the long run, but it will be hard to get it as a startup. You will need to organize the entire company around SEO to win, by making SEO a core competency of the company.

Low Search Volume/Low Competition: Content Marketing

This is common with startups that are creating new products or product categories, especially in mobile apps. They do not have enough demand yet. The general approach here is to expand your keyword target to the broader industry that does have high search volume, and pursue a content marketing strategy around those keywords that mentions your product/service occasionally in them.

Low Search Volume/High Competition: Ignore

Feel free to ignore SEO as a strategy here unless something changes.

This allows us to build a 2×2 to express SEO strategy options:

Step 3: Actually Working on SEO

Assuming you’re not in the low search volume/high competition bucket, you’ll want to start figuring out how to work on SEO. To do that, it’s helpful to make sure we define what we’re doing. Search engine optimization is the process sites use to appear in the organic results of search engines. To have a process, you need to understand what search engines do.

1) Search engines use crawlers to discover pages across the web.

2) They read any content they can find (mostly text)

So, in order to succeed, you need to be discoverable and readable. Once your page is discovered, search engines determines the authority of the page

Once your page is read, search engines determines what the relevance is for certain searches.

Determining Relevance: On-Page Factors

So how do search engines determine relevance? Well, here’s a rough hierarchy. They look at the title tag of the page first then the H1’s and H2’s, thing that typically indicate importance in HTML. Then they read normal text, and they look at what the URL says. They also look at this page compared to all the pages in their index and see how unique this page is compared to the rest. Search engines prefer unique content. They also look at the last time the page was updated. Frequently updated pages are seen as more reliable to Pinterest. They also look at the # of links on the page. A page with a ton of links is associated with a worse user experience and having less relevance. They also look at where the keywords are on a page. Google breaks up the page into header, footer, sidebars, and content area. Keywords in the content area are weighted higher. They also look at the # of content types. A page with text, video, and images is seen as better than just a page with one of those. They also look at the # of ad blocks on the page. A page with a bunch of ads is seen as less relevant. I know that sounds like a lot to pay attention to, so just keep this short list handy:

Title Tags

HTML Tags

Text

URL of the page

Uniqueness

Freshness

Number of Links on the Page

Keyword location on the Page

Diversity of content types

Number of ad blocks on the page

Make no mistake about it. This is mostly engineering work. You have to be messing with your site to get it to rank better. Mostly, this means creating pages specifically for keywords you want to target, and optimizing the above for these pages. I have seen so many startups think they can cover SEO by hiring a marketer to manage it. Unless they get engineering help, it will not work.

Note: this is what you check to answer if your keywords are competitive in Step 2.

Determining Authority: Off-Page Factors

So, how do search engines determine authority? Well, the main two things are quantity and quality of external links to the page and domain. Search engines see links as votes, so if another site links to you, that’s a vote that you’re an authority. Now, not all votes are ranked equal. A link from the San Francisco Chronicle will be worth more than a link from my blog. They also look at how other sites link to you. So, the anchor text is very important. If a link says home decor, that will help more than a link that says click here. They also do look at internal links within a site. So, us linking to something from our home page indicates that we think it’s very important, where as a link from our Help page is not as important. Search engines also look at the data they accumulate about a page. So, when a page gets clicked from Google, they look at the bounce rate. When Google shows a page in a search result, they also look at its click through rate. They also look at which parts of the page people link from. A link from the content area of another page is worth more than a footer link. They also look at the diversity of link types. A page that gets links from blogs, news sites, and social media will be better than just a bunch of links from blogs. Too much detail again? Don’t worry; I have you covered with another list:

Quantity of external links pointing to page/domain

Quality of external links pointing to page/domain

Anchor text of links

Internal links pointing to the page

Metrics from search engines (bounce rate and click through rate)

Area on page of internal/external links

Diversity of link types

If you’re building a good company, this is mostly public relations and business development work. Also, if you’re working on content marketing, the quality of the content alone can drive links, which is why you see every company trying to push their infographics everywhere. Widgets have traditionally been a strong strategy here that may be waning in importance.

Appendix: Tools at Your Disposal

Now, search engines give you some tools to help you do this. So, I’ll describe them.

Google/Bing Webmaster Tools: These destinations give you a host of information on keywords you rank for, crawl rate, errors etc.

Meta Tags: By default, search engines will use your title tags and meta descriptions to populate how your listings appear on their sites

Sitemaps: This is a way to send search engines every page you want them to index instead of waiting for them to find a link to it. No guarantee they’ll index all those pages, but they’ll look at them.

Nofollow Tags: With the explosion of user-generated content and social media, spammers started flooding these sites with links to rank on search engines. Given that it’s very hard to monitor all that content, search engines allow sites to add rel=nofollow to outbound links, saying you can’t vouch for the site you’re linking to. Pinterest uses nofollow to external links as do most other social media sites.

Canonical Tags: another cool tag. As we said before, Google likes unique content. But Google may figure out how to access the same content from multiple URL’s. If that happens, when Google finds a duplicate version of a page, you can add the rel=canonical tag in the head to indicate that if this page gets a link, use it for this other URL with the same content.

Hreflang Tags: helps tell Google which version of a page to show users in different languages and countries.

301 redirects: URL’s change all the time. But if a URL changes, normally that would be considered a new URL that needs to generate its own authority. If you 301 redirect the old URL to the new URL, Google will transfer some of the authority of the old URL to the new URL.

robots.txt: Search engines obey operatives in your robots.txt file or in meta robots on which pages to crawl or index.

Rich snippets: This will show different content under your listing, like star ratings and other meta data to help your listing stand out.