I’ve had the pleasure of speaking at TCV’s Engage Summit the past two years. The Summit gathered ~40 CPOs and product leaders to chat through topics centered around product development and product-led growth. This year, topics ranged broadly from incorporating AI to deliver world-class consumer experiences to defining and measuring different forms of community-powered growth. I never posted my talk from last year, so I’m adapting it into a blog post here, and will do the same for this year’s talk in the following weeks and as well as some follow up questions from the Summit I’ve had a chance to ruminate on.

Also, I publish on Substack now! So subscribe here.

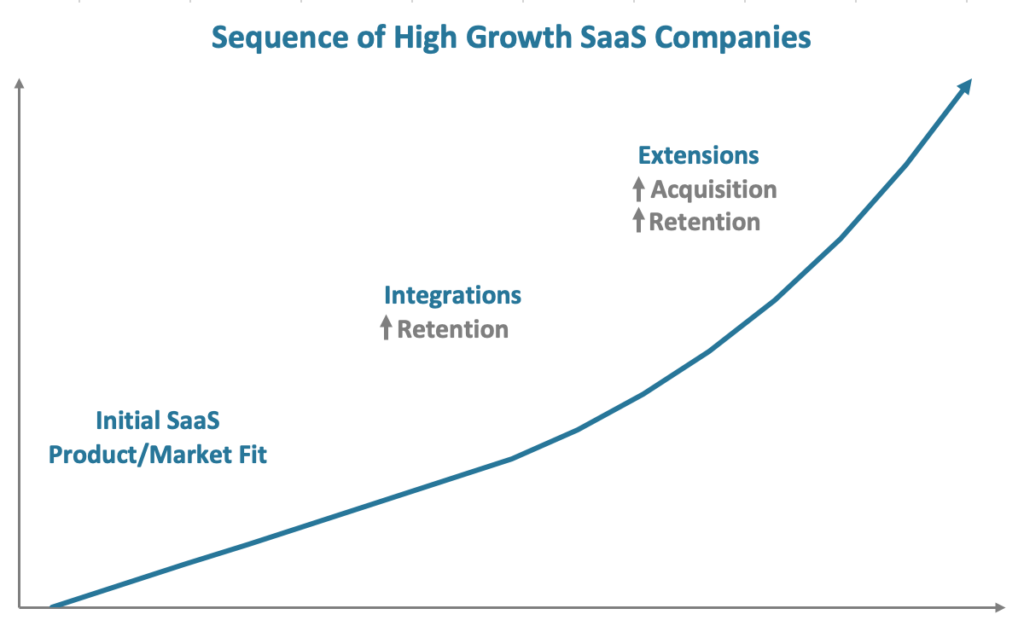

After product/market fit, most companies’ obsession is not thinking about how to create their next amazing product. Their obsession is thinking about growth. Specifically, how do I get this product I know is valuable in the hands of everyone it can be valuable to. Most companies have a primary acquisition loop that drives this scalable growth, and unfortunately, there aren’t that many acquisition loops that really scale. Even when they scale, they eventually asymptote, and companies need to find new ways to grow. This can be new growth loops for the same product, or entirely new products. In this post, I’ll explain how to think about the timing of that, and show some of the successes and failures of my career.

As I have discussed in previous essays, product/market fit can be hard to interpret at the time. When you find product/market fit, problems don’t go away. Customers don’t stop complaining. In fact, they complain more, because they like the product enough to care. What they stop doing is leaving. And you start being able to acquire more of them in a scalable way i.e. an acquisition loop.

Because of this and other factors, when you find product/market fit, you can’t stop iterating. Product/market fit has a positive slope. If you find product/market fit and don’t continue to make the product better, a rising competitive landscape and customer expectations can have you fall out of product/market fit over time. But when you do achieve product/market fit, while you don’t stop iterating, your portfolio of what you work on needs to change.

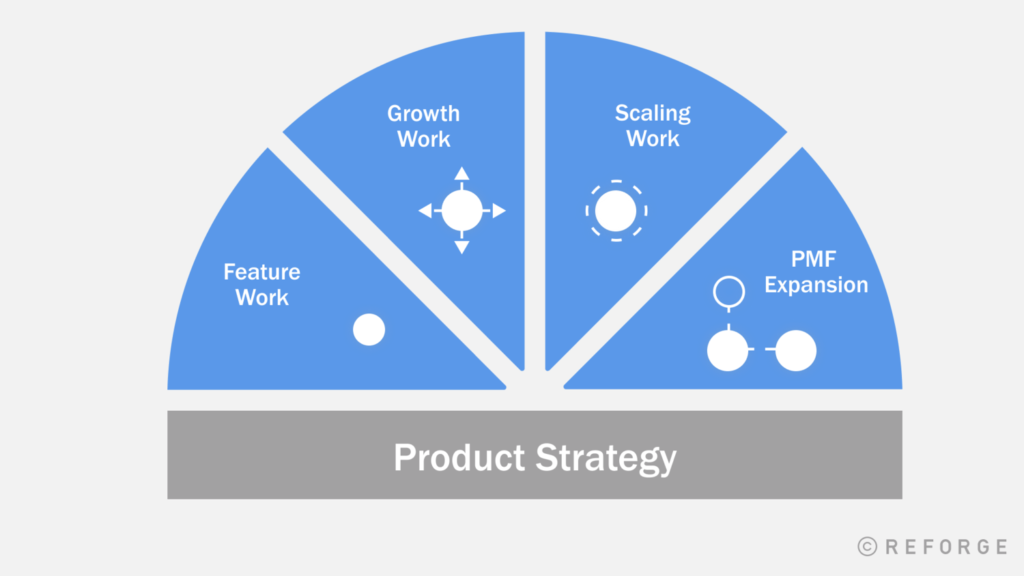

At Reforge, we talk about the four types of product work. Once you find product/market fit, zero to one product/market fit work goes away entirely for a while as your portfolio shifts to different types of product work:

- Features: improve current product/market fit

- Growth: connecting more people to existing product/market fit

- Scaling: being able to scale the product to more users and more teams internally

- Product/Market Fit Expansion: new segments, markets, and eventually products

The growth work in particular becomes a major focus, strengthening and discovering new acquisition and engagement loops. Most companies when they find product/market fit with their first product only have one acquisition and engagement loop that is successful, and the job of most of the team is to refine and scale those loops. At Pinterest, I was originally in charge of building a new acquisition loop built on top of Google. It looked like this:

We eventually re-architected our engagement loops to be based around personalization instead of around friends. When you stitch these acquisition loops and engagement loops together, it creates a more complicated growth model that looks like this:

The acquisition loop now feeds new users into a personalization loop that increases engagement over time, and emails and notifications reinforce that loop by distributing relevant content to users outside the product to bring them back. The entirety of Pinterest for the first few years I was there was tuning these loops in one way or another. Eventually, the company needed to layer in new advertiser focused loops to monetize, but I’ll skip that detail for now.

When I arrived at Eventbrite, the company was a lot more mature than when I started at Pinterest. But similar to Pinterest, it started with one acquisition and engagement loop driving its growth.

Creators market their events to bring in new ticket buyers. Many of those ticket buyers, once introduced to Eventbrite, start creating events themselves. And when event creators are successful at selling tickets, they come back and create more events. But Eventbrite didn’t stop there. It kept investing in making its overall growth model stronger.

Why did they do this? Well, all growth loops eventually asymptote. If you get good at modeling your loops, which basically takes the diagrams above and turns them into spreadsheet based forecasts of the impact to your business, you can start to predict when they will stop driving the growth the company needs. Modeling both helps you predict when those asymptotes will happen and unconstrain those loops by finding their bottlenecks and alleviating them. At Pinterest, we 5x’d conversion rate into signup over time, and doubled the activation rate of signups to engaged users over time as a couple of examples.

Some constraints in your growth loops can’t be fundamentally unconstrained by optimization though. The company requires either new growth loops or new products to acquire, retain, or monetize better. Modeling your loops helps you start investing in building out those new growth loops or products well in advance of when you need them to sustain your growth, because of course developing them takes much more time than improving a current loop. We think of this as sequencing different S-curves of growth.

By my arrival as an advisor by 2017 and CPO by 2019 at Eventbrite, the company had layered on many more acquisition loops onto its original loop to continue to grow, creating a much more complicated growth model.

Now, I know this looks complicated, but all that is really going on here is Eventbrite took its monetization of ticket sales and re-invested all of that money into new acquisition loops to bring in more event creators (sales, paid acquisition, content marketing). Also, Eventbrite took the increasing scale of event inventory created on the platform and started distributing it themselves to drive more ticket sales per event to places like Google, Facebook, Spotify, and its existing base of millions of people who had bought tickets to previous events.

People don’t talk enough about how much S-curve sequencing work went on at all these successful companies, so I wanted to give you a taste of what it looked like across my experience at Grubhub, Pinterest, and Eventbrite because it’s a lot, and a lot of it didn’t work. Let’s start with Grubhub summarizing ten years of decisions that both helped and hurt Grubhub as it scaled to be a public company (+’s show up where I think the decision helped, and -’s where I think the decision hurt):

- 2004: Grubhub co-founder collects menus of Chicago neighborhood restaurants, scans them, and puts them online (+)

- 2005: Grubhub expands to cover all of Chicago (+)

- 2006: Grubhub launches online ordering from restaurants (+)

- 2007: Grubhub optimizes sales model and expands into second market (+)

- 2008: Grubhub unlocks demand side channels and refines expansion playbook (+)

- Grubhub launches Boston and New York (+)

- Grubhub landing pages for restaurants that deliver to X start ranking well on Google (+)

- Grubhub unlocks paid acquisition to drive demand (+)

- 2009: Grubhub scales market launch playbook (+)

- Grubhub switches from flat fee to percentage model (+)

- 2010: Grubhub launches pickup (-)

- It doesn’t find product/market fit and hurts delivery use cases (-)

- Grubhub now launching at least one new market per month (+)

- 2011: Grubhub acquires Campusfood and launches restaurant websites (+)

- Grubhub acquires Campusfood to expand to many college markets (+)

- Grubhub acquires Fango to build in-restaurant tech (+)

- Grubhub launches restaurant websites to drive in-restaurant growth (+)

- 2013: Grubhub acquires Seamless (+)

- 2014: Grubhub goes public and starts building a delivery network to compete with Uber and Doordash (+)

- It doesn’t matter as those companies raise billions of dollars to destroy Grubhub’s network effect (-)

What you can see here is despite a successful outcome of an IPO and $7.6 billion exit, Grubhub made a lot of mistakes. If you strip those mistakes out, the sequencing of S-curves looks like:

The main lessons that matter here to me are that Grubhub tried product expansion too early with pickup. But market expansion became a major strength and well oiled machine through sales and SEO expertise as well as strategic M&A. That strategic M&A failed them, however, in responding to the threat of delivery networks. Grubhub was integrating its largest acquisition when Doordash and Uber Eats rose to prominence, and while Grubhub acquired over a dozen companies, it never acquired the one that was truly disruptive (Doordash).

Okay, let’s do Pinterest in the same format:

- 2010-2011: Founder visits DIY/Craft Meetups and convinces Influencers to start “Pin It Forward” Campaign (+)

- This gets people to learn how to use the “Pin It” functionality in their browser (+)

- Pinterest uses Facebook Sign-In to bootstrap network of friends as more people join the platform (+)

- 2011-2012: Pinterest leverages Facebook Open Graph to share every Pin into users’ Facebook feeds (+)

- Pinterest starts to amass enough content to make discovery, not saving, primary value prop (+)

- Retention and frequency of use improve (+)

- 2013: Facebook turns off Open Graph and growth stops (-)

- 2014: Pinterest fails to unlock growth with new products, but does unlock User Generated Content distributed through SEO (+)

- Pinterest launched a maps product, a Q&A product, and a messaging product, and all fail to drive growth (-)

- Pinterest finds another channel in Google to distribute its high quality content to after Open Graph turned off by Facebook (+)

- Users come in with less match to existing network, so friend graph ceases to drive ongoing discovery. Retention decreases. (-)

- 2015: Data network effects kick in (+)

- While friend graph ceases to work, Pinterest now has the scale of content to recommend great content just based on users’ interests. Moves to interest, not friend based discovery. Retention improves again. (+)

- Pinterest pauses all U.S. work to make sure we unlock international markets (+)

- Pinterest tries to re-ignite user sharing and fails (-)

- 2016: Pinterest crosses 50% international active users (+)

- Focus shifts to building advertising business to make money (+)

- Growth team starts seriously experimenting with paid acquisition as new channel (+)

Despite Pinterest being worth *check’s today’s stock price* $21.5 billion on the public markets today, you still see a lot of the mistakes we made. Too much new product development that didn’t pan out and too much trying to regain what we had lost vs. leaning into new areas that were working. Network effect products rely less on new product innovation unless it’s the only way to monetize. And Pinterest tried the harder expansion before the easier ones. Market and category expansion tend to be much easier than product value expansion. But, Pinterest did make a very successful pivot from direct network effects to data network effects and from Facebook to Google as the primary distribution channel. When you strip the failures out, our success looks like the following sequence:

Okay, for the last one, let’s do Eventbrite:

- 2006: Eventbrite launches to allow event creators to accept payments online (+)

- 2007: Event creators start putting $0 in the payment field to create free tickets, driving huge awareness (+)

- 2008-2012: Eventbrite builds more features to help event creators run their business and includes them in ticket fee (-)

- 2012: Eventbrite builds sales team to scale to more upmarket event creators (-)

- Eventbrite launches new countries with sales-led strategy (-)

- These countries never build the self-serve growth motion of the U.S.

- 2016: Eventbrite launches consumer destination to help consumers find events (+)

- SEO landing pages featuring events in different cities become large drivers of ticket sales (+)

- Eventbrite begins scaling emails to consumers of events they might be interested in (+)

- 2017: Eventbrite launches packages and acquires Ticketfly to move upmarket into the enterprise music segment (-)

- Packages makes Eventbrite more money in the short turn, but drive churn and less acquisition over time (-)

- Many Ticketfly customers are a poor fit for Eventbrite from a service / functionality perspective. Segment is low growth. (-)

- 2018: Eventbrite acquires Picatic to build developer platform (-)

- 2020: Pandemic hits, and Eventbrite rewrites strategy to focus on independent, frequent creators and help them grow

- Focus on self-service and helping creators drive demand

- Cancel separate music product and developer platform

- 2021: Eventbrite launches Eventbrite Boost, a suite of tools to help creators improve their own marketing

- 2022: Eventbrite launches Eventbrite Ads to help event creators reach more consumers searching for events on Eventbrite

Since this shift is happening in real time, I’ll describe the S-Curve sequencing Eventbrite was investing in as of the end of my full-time role. The value prop is shifting from payments and ticketing to helping event creators grow their ticket sales. Eventbrite has launched new pricing with tools like marketing tools that help event creators get better at their own email and performance marketing as well as let them get more distribution inside Eventbrite’s platform. The revenue from this will help drive more investment in the consumer product side of Eventbrite, which hopefully drives more consumers looking to Eventbrite to find things to do and buying more tickets from our creators.

Hopefully you see from these examples that sequencing S-Curves to drive growth of companies over the long term is not only quite difficult, but the craft of doing it is under-developed. All three of these companies made some critical successful moves as well as major mistakes that set them back years. I hope that by studying these and other examples startups can get smarter about how they sequence their S-Curves and drive long term success for their companies. In my next two posts, I’ll go deeper on how to think about how platform shifts like AI affect this and publish a lot more on when and how to invest in building your second product successfully.

Currently listening to my Rhythym & Bass playlist.

And don’t forget to get on my Substack list for future posts here.