Quite a few people have asked me recently how to scale their marketing efforts. The short answer is: as leanly as possible. I have realized that while many entrepreneurs intuitively understand that statement, they do not understand what that means in terms of what types of marketing you try and in what order. I have developed a framework to easily identify how to think about this process that scales across different types of startups that I will present below.

Pre-amble I: The Three Costs

The first thing that’s important to understand before delving into this framework is that lean = with as little cost as possible, and that costs come in three areas: marketing expenses, development expenses, and payroll expenses. Marketing expenses are pretty easy to explain. If you spend $5,000 on Google AdWords this month, and each ad promised $5 off, your marketing expenses are the $5,000 for AdWords plus $5 times the numbers of conversions that redeemed the $5 off promotion. Development expenses are a little more difficult. If you outsource development, it may be easy to think that the development expenses are how you paid your developers, but that would be incorrect. The real issue here is the opportunity cost. Whether you have your own developers or outsource, if your developers work on, say, SEO initiatives, that is time they are not spending on new features for your customers, infrastructure scalability, et al. The third cost is payroll expenses. This is the cost relating to paying the marketing people on your team. Early on in startups, payroll can be the largest expense, so adding people to your team, especially in marketing, needs to be carefully considered as payroll expenses are harder to adjust than marketing or development expenses. The only way to adjust them is to fire someone or reduce their salary, and both can have a negative effect on employee morale and company culture.

Pre-amble II: The Metrics

After you understand costs, you need to understand the metrics on how to evaluate marketing decisions. For startups where a customer pays you for a product or service, this is a little bit easier than if you have yet to determine a business model. A couple key metrics for me (forgive me if some of this is basic):

CPA (Cost per Acquisition): For this metric, you take the amount you spend in marketing expenses, and divide it by the number of new customers you acquired. So, in our previous AdWords example, let’s say I acquired 500 customers with that effort. That would make my CPA:

Cost: $5,000 + ($5 * 500) = $7,500

New Customers: 500

CPA: Costs/New Customers: $15

Revenue/User/Time frame: The CPA is not very meaningful until you know how it compares to the revenue those new customers brought you. The important thing here is not to just compare the revenue of the initial sales of that customer if they are likely to purchase again. If they are likely to purchase again, use cohort analysis to determine how much in revenue those new customers will make you over a certain time frame. The obvious question is how long a time frame should I use to compare against CPA. The short answer is as long you can reasonably predict. So, if you have enough data for a marketing channel to accurately predict how much a new customers from a new channel will make for your business over a two year time frame, you should feel comfortable comparing to a two year value. In reality, a startup almost never will have the data to accurately predict that far ahead. At the start, you may only have three months of reliable data. Reliable means both statistically significant i.e. not just 12 customers, but a reasonably sized population, and a situation where historical customers are representative of the newest customers. Once a startup reaches some scale, the latter requirement is the hardest. As a startup attracts more and more new customers, it typically has to start targeting customers that are less likely be early adopters and less likely to experience the pain your product solves as acutely as those who found it early on. Both of which will likely make new customers today less valuable than new customers from a year ago, keeping all other variables static. I almost always advise startups to keep their revenue metrics to a year or lower. After a year, you are waiting a very long time to prove your assumptions correct, and need to start discounting for the time value of money.

Volume: This basically asks is a marketing channel generating 12 customers or 1,200. This will determine how to prioritize resources among marketing channels.

Potential: This asks if a marketing channel has room to grow, and just needs more budget/people/development resources to achieve that potential, or is it already maxed out.

Marketing Profit: In this sense, profit equates to Revenue/User – CPA. Channels that have high Marketing Profit are going to be the areas you want to invest more time/money/people in, if the potential has not been reached and the volume is significant.

Note: Some marketers may want to add in the promo costs not in CPA, but subtract it from the revenue side. I dislike this approach, as it increases variability on both sides of the CPA vs. ARPU model, which makes it harder to compare the effectiveness of specific marketing channels just by looking at CPA.

Phase 1: Product Driven Growth

Scalable, Measurable, Engineering Opportunity Cost Driven

The leanest way to acquire customers is not to spend any money on them and not spend any money on marketing people. The chief ways to do that are to use the product you have already built to acquire more customers. There are four main ways:

Product Quality: This is the case where your product is so damn amazing that every person that uses it naturally tells everyone they know about it, and that’s what drives growth. In another, this is the build it and they will come strategy. Also known as a pipe dream. But improving the core product every day helps grow it, and people sometimes forget that.

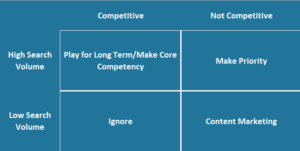

Search Engine Optimization: This is the process of designing your site to appeal to search engines to rank for relevant queries to your business. Depending on the business, this may be a large opportunity or a very small one, and a very crowded space or a relatively sparse space. The main question to ask is: are people on search engines currently searching for keywords that closely match the product or service I provide? If so, can I reasonably expect that by designing by site using Google best practices with some well placed content that I could rank in the top five for any keywords that in aggregate would drive a meaningful amount of new customers? You may offer a product with a ton of keywords, but heavily competitive for SEO e.g. consumer real estate, or a product with no keyword volume, but also sparse for SEO e.g. a technical solution for resin casting.

Referrals/Viral Loops: This is the tactic of asking current customers to invite others to the service, perhaps offering a financial or psychological incentive. This is a fairly low development tactic with high upside and little downside, so it is very popular.

Conversion Rate Optimization: This is the process of making continual changes to a website/mobile app/landing page with the goal of increasing the amount of visitors who turn into conversions. The only costs here are development costs, but the effects are very measurable. This may be difficult to do until you have enough traffic on your site accurately measure lifts in conversion rate.

Main constraint: Development resources

What should happen here: You start here, iterate as much as you can until your development pipeline gets too clogged. Then, as you wait for development to catch up, you move onto Phase 2.

Phase 2: Performance Marketing

Measurable, Scalable, Marketing Budget Driven

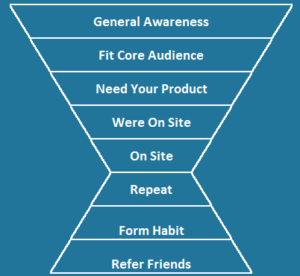

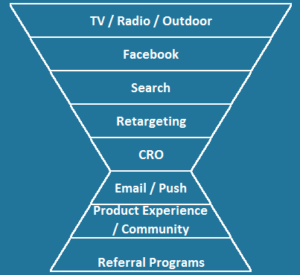

The next leanest way to acquire customers is to develop marketing systems that, once created, can scale from driving dozens of new customers to thousands with the only additional input being more marketing expenses. Early marketers in a startup can focus on marketing efforts that scale without having to hire more marketers and have vast potential. If you don’t have a business model yet, most of these tactics (besides email or push notifications) will be off limits, as you will have no Revenue/User/Time frame to compare CPA’s against.

Search Engine Marketing: This is targeted specific keywords on Google and Bing and bidding to show an ad for your product or service to potential new customers at the top of the page. Like SEO, you need to determine if the search engines have enough search volume to make this an effective channel. You also need to determine how expensive it is for you to bid on keywords and convert them. If there is a lot of search volume and not a lot of competition, this can be a very effective way to drive customers, and is very trackable to CPA goals down to the ad and keyword level.

Email Marketing: This is sending either mass or, preferably, targeted and personalized emails to your existing user base to either convert them into a paying customer or entice repeat purchases. This is probably the most cost-effective and under-utilized tactic for most startups.

Online/Mobile Display Advertising: This is showing banner ads on websites and mobile apps. Most startups use retargeting to reach people that have already been to their site but not converted. More sophisticated startups are experimenting with real time bidding to find ad impressions that are likely to reach their target market. The challenge here is determining effectiveness of spend as few people click ads, and correlating views to purchases is a dicey proposition. There is near limitless inventory to spend on if you can determine effectiveness.

Main constraint: Money and diminishing returns

What should happen here: You experiment with a few paid, scalable channels, find the ones that work, and scale them until you see diminishing returns. If your team still has bandwidth, then you have them contribute with Phase 3 tactics. If your team doesn’t have bandwidth to scale these techniques, but they work, you should hire a dedicated resource for them.

Phase 3: Brand Marketing

Non-Measurable, Non-Scalable, People Driven

These are techniques that have one-time value, and/or require not just increased investment, but also increased resources (read: people or development) to scale. They are also frequently going to only work in one market or for one type of customer.

Content marketing: Content marketing has many names, but is the creation of blog posts, articles, videos, of infographics that are of interest to your target customer. They can be great content to help rank for SEO, especially if your business does not have more direct keywords to target. It is even more impactful as content for social media or distribution to media outlets. It is non-scalable because if you want to do more of it, you have to produce more of it, and it’s time consuming to do it well unless it’s user-generated.

Out of home: This is the process of buying billboards, bus shelters et al. out in the real world and placing ads for your business in them. This can be very expensive, but also very valuable if there’s a way to use them to target a very valuable audience e.g. hungry urban professionals right before dinner in GrubHub’s case. It’s non-scalabale because only certain geographies will have good opportunities, and what will work in one geography may not even be an option in another.

Community management: This is either using a section of your site/app or more likely social media channels such as Twitter and Facebook to communicate with your audience in conversations they are interested in having with you. This is a great way to provide quality customer service and create evangelists. It is non-scalable as it requires a dedicated resource to monitor these channels, and as you scale, to keep up quality, you need to add more dedicated people for it.

Public relations: This is the process of getting news outlets to showcase you. It is non-scalable because it provides a bump, not an engine, requiring constant efforts to make it a consistent source of traffic.

Marketing promotions: This is the process of a creating a compelling campaign that attracts people to your business, whether it’s a contest, event, etc.

Main constraint: People

What should happen here: Use your existing team to determine which of these is important for your company, and then staff accordingly.

Running All Three Phases

These phases do not imply that you focus all of your efforts on phase I, max out, and then move onto the next phase. The reality is that the constraints of the various phases set in quickly. So, it could that in close to no time at all, you are executing programs in all phases. This blog post just provides the framework for prioritization and best practices for maximizing how you grow your marketing programs.