I recently appeared on GrowthHacker.TV to discuss my experience at GrubHub and Pinterest. Check it out here.

Currently listening to Kyle Bobby Dunn & The Infinite Sadness by Kyle Bobby Dunn.

I recently appeared on GrowthHacker.TV to discuss my experience at GrubHub and Pinterest. Check it out here.

Currently listening to Kyle Bobby Dunn & The Infinite Sadness by Kyle Bobby Dunn.

Frequently people ask me how our growth team is structured at Pinterest. In our case, it is a cross-functional team. Engineers, product managers, analysts, and designers all work together on shared goals. Pinterest believes the best results arise when people from different backgrounds work together on a problem. I’ve thought a lot about how to develop effective cross-functional teams in an organization, and I’d like to show how to do that successfully. These, in some ways represent how Pinterest is structured, and in other ways, don’t.

Step 1: Define Metrics

In order for a cross-functional team to be successful, it needs a North Star metric. If you’re creating one broad team, it’s a broad metric, like MAUs or revenue. I prefer creating multiple, smaller cross-functional teams that carve a piece out of the main goal, like signups or new user revenue. Then, you can create another small team for something like retained users, or repeat user revenue.

Step 2: Build the Team

A core team for cross-functional team trying to impact a metric is usually:

Engineer

Designer

Product Manager

Analyst

Potential other members:

Marketer

QA person

Researcher

Depending on the goal, you may not need many of these, or the product manager can be the catch all for analysis, research, etc. One person should be the owner of the team. Usually, this would be the person with the most context. At Pinterest, it’s either an engineer or a product manager. Ownership should seem arbitrary as the team should organically align on initiatives over time, deciding between short and long term projects, based on a shared understanding of what is likely to move the key metrics. So, ownership is more so management has one person to go to with questions than anything related to authority.

Step 3: Re-train Managers

There shouldn’t be any managers on cross-functional teams. Managers are the glue between different cross-functional teams, making sure all the teams align to the global strategy, and don’t improve their metrics at the cost of another team’s metrics, which is easy to do. Here is what some managers roles will look like in this scenario:

Design Director: align visual style across the entire application

Director of Analytics: align use of tools across teams for easy translation of data back and forth and sharing of pertinent data across teams

Marketing Director: allocate budget effectively, communicate how teams’s activities affect each other and balance

Director of Product: ensure product opportunities on one team can be leveraged by other teams, prevent disjointed product experience

Benefits of Cross-Functional Teams:

1) Improvement of cross-departmental communication: You would be amazed at how quickly individual contributors of different teams start to understand other department’s needs once they sit with them for a while and work on a shared goal. The marketer starts to understand why having dozens of tags firing is bad for the engineer. Once designers internalize the metrics from analysts, they start to work differently, and get satisfied by moving metrics instead of how beautiful their design is. The engineer sees how hard it is for the analyst to measure impact and starts to design better tracking systems and design better database storage.

2) Better ideas: The best ideas typically come from the intersection of people with different backgrounds working together on a problem. Designers, engineers, marketers, analysts et al. think differently. They solve problems differently. They have different strengths and weaknesses. Having them work together on problems almost always ensures a more optimal result.

3) Better prioritization: Instead of a product manager getting a list of requests from various teams, all those stakeholder are actively brainstorming together and measuring projects on potential impact to the metrics.

4) Increased speed: When teams aren’t spending time coordinating with other teams, disagreeing on goals and priorities, and struggling with inefficiencies, they produce results much faster.

Currently listening to Through Force of Will by Torn Hawk.

I don’t think there’s anything I’ve heard people complain more about than co-workers or managers or employees they don’t get along with. People tend to categorize their co-workers as pure good or evil, leading to toxic relationships. Sometimes, these perceptions start from a simple misunderstanding that goes unresolved and grows over time. Sometimes, work styles are just incompatible. Most workplace relationship advice I had heard previously focused on getting to know the “real” person. Friendship, it seemed, was the only key to working better with these people, and friendship could only be attained by learning about people’s families, their passions, etc. This always felt forced to me, and when people attempted it on me, it felt manipulative. Also, some of the most effective teams I’ve worked on did not have this friendship. If that process works for you, stick with it. But if it doesn’t, let me tell you a story about how I learned to build more effective relationships at work.

When we hired our VP of Marketing at GrubHub, it created two problems for me. The first was I had gotten used to not having an active manager and doing things my own way. The second was I had developed a very direct style from working closely with the founders and other members of the team for a long time. As I continued my normal working style, that created problems for my new manager. She didn’t appreciate the direct tone of my emails, interpreting them as harsh criticism of her and others. She didn’t like the way I evaluated ideas. She liked short bullet points for emails. I tended to write paragraphs that covered a lot of details. Things went on like this for a few months, until she basically told me I had to change. This is a moment every employee should understand. The manager has communicated some feedback, and you can either ignore it and likely get fired, or apply it and stick around. So, the rule for building effective relationships with managers is to adapt to their style. They don’t have to adapt as they can just hire for people that fit their style.

After I adapted, I began to build a better relationship with my manager. She really valued personal growth of her team. So, as part of her process, we examined all of the issues I was having at work on a quarterly basis (which I highly recommend). When I was having an issue with a certain junior person at work, I described how this person operated, where their shortcomings were, how they needed more direction, how they responded to my requests, etc. She gave me some advice that really resonated: “Assume that person won’t change. How can you change to work with this person most effectively?”

As members of the workplace, it’s easy for us to see the flaws in how other people work. We spend a lot of energy hoping that those people will improve their performance in these areas. This is wasteful energy. While you should give direct feedback whenever possible, you can’t assume it will be heeded. So, you have to think about what you could change in how you work with someone to be more effective as a combined team. Sometimes, very simple changes can make all the difference. The only way to do this is to try different approaches and see what works and what doesn’t. Many people do this with their managers, but it’s even more critical to do it with your other co-workers. Identify the issues, brainstorm other approaches, and test them.

I think a lot about how to create and maintain highly effective teams. To be a part of a highly effective team, you need to have mutual trust with your team members. Many companies approach this problem organizationally, but the more I’ve thought about it, the more I’m convinced individual tackling it one co-worker at a time is the right solution. So, I thought about what trust really means with your co-workers, and found that there are really different levels of trust in an organization. I’ll break them down here.

Layer 1: Same Goals

It’s amazing how many workplace relationships never even get to this step. I’ve been lucky to work with really exceptional teams with shared objectives and aligned incentives, but the first question you should ask when trying to establish trust with a co-worker is, do you really have the same goals. In more political organizations, co-workers tend to see things as zero sum. If she gets what she wants, I won’t get what I want. This can be related to project allocation, budgets, headcount, etc. Even in non-political organizations, I’ve found other people tend to assume we don’t share the same goals.

So, what do you do if you don’t share the same goals? I have tried to break down what we’re trying to accomplish to find some middle ground. Usually, people are at companies for at least some similar reasons. If you have frank conversations with your co-workers, you can typically find those out and build from there.

Why is it important to have the same goals? If you don’t, you can never be confident a co-worker won’t undermine you/your plans, try to make you look bad, get you fired, etc. This sounds kind of rash and unrealistic, but you’ll be surprised how often these things happen.

Layer 2: Doing What You Say

Once you’ve agreed to the same goals, you need to divide work to reach those goals. The second layer of trust is having confidence that if someone has said they will do something, they will actually do it. This probably sounds minor, but it’s probably a more common problem than sharing the same goals. Co-workers are constantly bombarded with tasks, and can easily get side-tracked. Some people also over-commit regularly and let co-workers down. Some people really mean to get stuff done, then when they excitement wears off, they get lazy. If you can’t trust someone to accomplish what they say will accomplish, you will not have a successful partnership with them. Now, it’s important that you commit to this as well. You can’t have a successful partnership if you don’t care of your tasks as well.

Layer 3: Covering

A truly highly effective partnership is not just about having the same goals and doing what you say you will do, but also covering all the gray area in between what you agreed to do and what actually needs to get done. Consider a typical project. As a product manager, I may write the strategy doc or requirements I said I was going to write or do the appropriate research, and it may cover everything I talked about with the engineer I’m partnering with on the project. But, sometimes, it won’t really cover everything it should cover for the project to be a success. Not only could I have missed something, but there could be something that couldn’t be foreseen that’s really important to the success of the project. In that case, both me as the product manager and the engineer could have done everything we said we would do, and the project would still not be successful. Layer 3 is about covering for these gray areas. You want to feel confident in a team that if you forget something, your co-worker will catch it and address it. You need to be able to do the same.

It’s really stressful being in a role where you feel you need to be “always on”, and if that you’re not 100% perfect on everything you do, everything will fail. Covering is about have a team member that can pick up the slack when you miss something or when something comes up.

So, if you’re trying to build better relationships at work, think about which layer you’re at with your co-workers and how you can ascend to layer 3. If you build layer 3 relationships with multiple members on your team, you’ll execute at an extremely high level, and will be way more likely to succeed.

As I advise startups on growth, one of the most common questions I receive is “should we be working on SEO?”. At this point, I tend to remind them of the three phases of scaling startup marketing or show them Andrew Chen’s great post on the few ways to scale user growth. In today’s mobile-first landscape, with the limited scale of the App Store/Google Play, the answer is actually a bit more nuanced. So I created a guideline on how to answer this question for any startup.

Step 1: Keyword Research

The first question to answer when thinking about SEO for your business is “what should my business show up for?”, which really is asking the question, “what is my business about?”. Unlike branding, where the point is to synthesize that answer into as few clear words as possible, keyword research is about generating as many answers to that question as possible. These will be your potential keywords. I like to use the framework: who, what, when, where, how to answer this question. Let’s take the example of GrubHub:

Who: GrubHub, restaurant names we represent

What: food, delivery, menus, pizza, thai, indian, chinese

When: breakfast, lunch, dinner, late night

Where: every city, neighborhood, zip code, college covered

How: online ordering, mobile app, iphone app, android app

Take these words, combine them all into new keyword combinations in Excel e.g. “late night pizza delivery berkeley”, and check to see how much search volume they have. To do that, use the Google Adwords Keyword Planner. Click “Get search volume for a list of keywords”. Take the keywords from the exercise above and paste them in. Click “Get search volume”. Click on Keyword Ideas tab. You can also do this process again to find new keywords by clicking “Search for new keyword and ad group ideas” at the beginning.

You can now see how much search volume is closely related to your business. Search volume determines how much your prioritize SEO for your business. Now, there is no hard and fast rule for how much search volume there needs to be for you to get excited about it as an opportunity. It depends on purchase size, how much you want to grow, etc. Generally, I recommend taking all of those keyword’s search volume, assuming you can get a very small percentage of it to your site e.g. 1%, and seeing if that would make an impact on your business.

Now that you have an idea of the search volume for your business, you need to know how competitive that real estate is. Fortunately, Google estimates how competitive they think each keyword is next to the search volume estimate. It lacks the granularity I’d like, but it’s a good starting point. What I do in addition to looking at this gauge is do some spot searches and see what the results look like. Here, I’m looking for two things:

1) Are the results primarily businesses you would consider competitors or blogs?

2) Are the pages that are showing up well optimized for the keywords you searched or not? Are they dedicated landing pages or home pages? (I’ll go into more detail on how to measure this a little later in this post)

Step 2: Picking an SEO Strategy

Now, you should have an answer to two questions:

1) Do my keywords have a lot of search volume?

2) Are those keywords competitive or not?

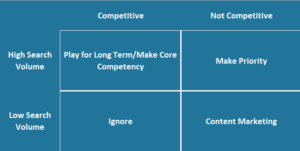

This creates four scenarios:

High Search Volume/Low Competition: Make Priority

This is a rare opportunity, and you can build a great business just off of SEO here. You should make SEO a priority and one of your primary growth strategies.

High search volume/High Competition: Play for Long Term/Make Core Competency

This means the ROI is there with SEO in the long run, but it will be hard to get it as a startup. You will need to organize the entire company around SEO to win, by making SEO a core competency of the company.

Low Search Volume/Low Competition: Content Marketing

This is common with startups that are creating new products or product categories, especially in mobile apps. They do not have enough demand yet. The general approach here is to expand your keyword target to the broader industry that does have high search volume, and pursue a content marketing strategy around those keywords that mentions your product/service occasionally in them.

Low Search Volume/High Competition: Ignore

Feel free to ignore SEO as a strategy here unless something changes.

This allows us to build a 2×2 to express SEO strategy options:

Step 3: Actually Working on SEO

Assuming you’re not in the low search volume/high competition bucket, you’ll want to start figuring out how to work on SEO. To do that, it’s helpful to make sure we define what we’re doing. Search engine optimization is the process sites use to appear in the organic results of search engines. To have a process, you need to understand what search engines do.

1) Search engines use crawlers to discover pages across the web.

2) They read any content they can find (mostly text)

So, in order to succeed, you need to be discoverable and readable. Once your page is discovered, search engines determines the authority of the page

Once your page is read, search engines determines what the relevance is for certain searches.

Determining Relevance: On-Page Factors

So how do search engines determine relevance? Well, here’s a rough hierarchy. They look at the title tag of the page first then the H1’s and H2’s, thing that typically indicate importance in HTML. Then they read normal text, and they look at what the URL says. They also look at this page compared to all the pages in their index and see how unique this page is compared to the rest. Search engines prefer unique content. They also look at the last time the page was updated. Frequently updated pages are seen as more reliable to Pinterest. They also look at the # of links on the page. A page with a ton of links is associated with a worse user experience and having less relevance. They also look at where the keywords are on a page. Google breaks up the page into header, footer, sidebars, and content area. Keywords in the content area are weighted higher. They also look at the # of content types. A page with text, video, and images is seen as better than just a page with one of those. They also look at the # of ad blocks on the page. A page with a bunch of ads is seen as less relevant. I know that sounds like a lot to pay attention to, so just keep this short list handy:

Make no mistake about it. This is mostly engineering work. You have to be messing with your site to get it to rank better. Mostly, this means creating pages specifically for keywords you want to target, and optimizing the above for these pages. I have seen so many startups think they can cover SEO by hiring a marketer to manage it. Unless they get engineering help, it will not work.

Note: this is what you check to answer if your keywords are competitive in Step 2.

Determining Authority: Off-Page Factors

So, how do search engines determine authority? Well, the main two things are quantity and quality of external links to the page and domain. Search engines see links as votes, so if another site links to you, that’s a vote that you’re an authority. Now, not all votes are ranked equal. A link from the San Francisco Chronicle will be worth more than a link from my blog. They also look at how other sites link to you. So, the anchor text is very important. If a link says home decor, that will help more than a link that says click here. They also do look at internal links within a site. So, us linking to something from our home page indicates that we think it’s very important, where as a link from our Help page is not as important. Search engines also look at the data they accumulate about a page. So, when a page gets clicked from Google, they look at the bounce rate. When Google shows a page in a search result, they also look at its click through rate. They also look at which parts of the page people link from. A link from the content area of another page is worth more than a footer link. They also look at the diversity of link types. A page that gets links from blogs, news sites, and social media will be better than just a bunch of links from blogs. Too much detail again? Don’t worry; I have you covered with another list:

If you’re building a good company, this is mostly public relations and business development work. Also, if you’re working on content marketing, the quality of the content alone can drive links, which is why you see every company trying to push their infographics everywhere. Widgets have traditionally been a strong strategy here that may be waning in importance.

Appendix: Tools at Your Disposal

Now, search engines give you some tools to help you do this. So, I’ll describe them.

Google/Bing Webmaster Tools: These destinations give you a host of information on keywords you rank for, crawl rate, errors etc.

Meta Tags: By default, search engines will use your title tags and meta descriptions to populate how your listings appear on their sites

Sitemaps: This is a way to send search engines every page you want them to index instead of waiting for them to find a link to it. No guarantee they’ll index all those pages, but they’ll look at them.

Nofollow Tags: With the explosion of user-generated content and social media, spammers started flooding these sites with links to rank on search engines. Given that it’s very hard to monitor all that content, search engines allow sites to add rel=nofollow to outbound links, saying you can’t vouch for the site you’re linking to. Pinterest uses nofollow to external links as do most other social media sites.

Canonical Tags: another cool tag. As we said before, Google likes unique content. But Google may figure out how to access the same content from multiple URL’s. If that happens, when Google finds a duplicate version of a page, you can add the rel=canonical tag in the head to indicate that if this page gets a link, use it for this other URL with the same content.

Hreflang Tags: helps tell Google which version of a page to show users in different languages and countries.

301 redirects: URL’s change all the time. But if a URL changes, normally that would be considered a new URL that needs to generate its own authority. If you 301 redirect the old URL to the new URL, Google will transfer some of the authority of the old URL to the new URL.

robots.txt: Search engines obey operatives in your robots.txt file or in meta robots on which pages to crawl or index.

Rich snippets: This will show different content under your listing, like star ratings and other meta data to help your listing stand out.

Read part 1 of of my series on loyalty marketing.

In my previous post on loyalty marketing, I talked about the different types of loyalty programs, and how to identify which type of program your company should pursue. Once that happens, do you slap up generic version of a program that tackles your needs and call it a day? Absolutely not. Now that you’ve identified a program type to target, you need to determine a version that your users will respond, that will fit your brand, is profitable over the long term, and is future proof. Let’s tackle user response first.

Understand Reasons Why

Your can’t expect your users to change their behavior until you understand why their behavior is the way it is. Let’s say most of your users use your product regularly, but not every time they have the problem you solve. In order to create a successful program, you need to figure out why they don’t use you the times they don’t. The only way to do that is to talk to them. Take random people in the segment you’re trying to change and arrange a phone call. Reward them for it. In 20 minutes, with targeted questions, you can learn all you need to know about the time they’re not using you. A standard question to learn this is “Tell me about the last time you did X and didn’t use us.” Keep doing these calls until you start hearing the same types of responses over and over. In my experience, things settle around four or five reasons. For loyal, but infrequent users, it works very much the same. Talk to users, but this time ask “Why don’t you use X for [new use case]?”

Understand the People Behind the Reasons, and Pick a Reason

These phone calls don’t give you any statistical representation around how popular these reasons are for the broader audience that isn’t using you every time. So, now that you have your reasons, you can survey the broader group, asking them, “When you do X and don’t use Y, which reason best describes why?” and make the answer multiple choice with the responses you received over the phone. With a good enough response, you can now stack rank the reasons why people aren’t loyal to you. Some may be product changes you need to make. Some may not be helped. But, more than likely, you can address most of them with an incentive. You can go further down the phone calls + survey rabbit hole until you have full personas of users. Knowing the reasons why users aren’t loyal and what types of users you have can make you say, “I want to target this reason for this persona.” The same philosophy applies to incentivizing use cases. Our survey question is the same question you ask over the phone, except now it’s multiple choice. The goal again is to be able to say “I want to target this use case for this persona.”

Testing the Program

Now, you’re ready to build a program. At this point, it’s mostly a creative exercise leveraging psychology. Invent a bunch of a programs that might incentive these users, narrow down the ones that are most likely to incentivize users and be profitable, and test. Email is a great way to test different programs because you don’t have to build much and can book keep manually to get enough data without users knowing it’s not a real thing. It is also not a bad idea to run your users through these program ideas over the phone or in person, but remember that what they say and what they’ll do may be very different. Still, talking to them can prevent some gotchas.

Once you have a program, you need to test in a live way. Depending on what type of program you build, you may be constricted. For example, Yummy Rummy at GrubHub was considered a sweepstakes, so we could not legally have a control group. A control group is always the best way to test. Sweepstakes laws are at the state level in the U.S., so if you have two states that perform very similarly, that may work. If you don’t, you need to measure pre and post data. Pre and post data is not ideal for a few reasons. The main one is that loyalty programs typically take time to change behavior, and if you turn them off, it will take time for behavior to change in reaction to that as well. You don’t want to be running the program for a over a year, and not be sure if your pre data is still relevant. What typically happens in these scenarios is that programs are pulsed, like the McDonald’s Monopoly game being available for a limited time yearly. There is too much money being spent on a loyalty program typically to not know for sure if it is working or not.

Long Term Success

One other dirty little secret about loyalty programs is that they tend to ebb in effectiveness over time. Humans are motivated by variable rewards, and if your program is static, your users may become used to it, and it may not create long-term behavior change. That is why I recommend creating a variable program. At GrubHub, we made Yummy Rummy available every three orders instead of every order, and the reward could be anything from a free drink to free food for a year. Furthermore, if you lost, you got a consolation prize that was something random from the internet. But, I don’t think that is even enough. You should strive to think of your program as constantly evolving to stay interesting to your users. This will make your program stay effective for longer as well as give you the flexibility to tweak elements to make it more interesting to you as the business. I have seen many companies stuck with a program they no longer think is effective, but too afraid to shelve it because of potential user backlash.

The other advantage of creating a living, evolving program is that, if the original incarnation is effective, you can change it to move users further up your user lifecycle. For example, let’s say you’re trying to incentivize platform use in your original incarnation of your program. You might be very successful at that, and then find an opportunity to take those same users and get them to use the platform more by incentivizing use cases. Now, you can do that by evolving the same program instead of starting from scratch. Or, you might have taken loyal users and gotten them to use you for more use cases. Now, you can adapt that same program to build a moat around them. This all boils down to what a holistic loyalty program should look like in three steps for most internet businesses:

1) Build loyal users in one use case

2) Increase frequency by incentivizing use cases

3) Build moat around those users

This happens to be how most marketplaces or social networks grow into behemoths. They nail an initial use case, build a loyal user base for that, gradually expand use cases, and then work to keep those users locked into their platform.

There seems to be a lot of confusion about loyalty marketing and how loyalty programs work. To an outside consumer, I guess the confusion is understandable. Most loyalty programs are branded as a value to the customer, a reward for their dedication. Most loyalty programs’ primary goals are not to add more value to consumers (though when they’re done well they do that too); their goal is to create more value for the company. I’ll break down how to think about loyalty if you are a business that is wondering if a loyalty program makes sense for you.

The first thing to understand is that every business has a loyalty problem; it just might not be the loyalty problem they’re expecting. To make this clearer, I’ll split consumers into four areas. Depending on where most of your company’s consumers fit is where you’ll spend your effort in thinking of a loyalty programs. The first thing to do is split all of your consumers into loyal and non-loyal and frequent and non-frequent. Loyal is defined by doesn’t use a close competitor as well as you for what your product/service does. Frequency is a bit more nuanced. Your product/service should have a target frequency you’re setting. For Pinterest, that might be daily. For GrubHub, that might be once or twice a week. You then can build a 2×2 matrix like the one below.

Each of these four buckets requires a loyalty program targeting different actions by consumers. Just to be absolutely clear, let’s go through that exercise for each segment.

Frequent, Loyal

Action: Keep consumers doing what they’re currently doing

Frequent, Non-Loyal

Action: Get consumers to migrate usage of competitors to you

Infrequent, Loyal

Action: Get consumers to use product/service more

Infrequent, Non-Loyal

Action: Determine if product issue can increase frequency. If not, ignore.

Now, we should talk about these strategies in a bit more detail. I’ll skip infrequent, non-loyal since it’s a combination of two other strategies, and probably implies a product or market problem.

Infrequent, Loyal Strategy: Incentivize Use Cases

In this segment, consumers use your product loyally, but not enough to your liking. This implies that there are not enough use cases for your product in the eyes of the consumer. That could be because these use cases do not exist, or because the consumer doesn’t perceive them to be relevant. If the use cases do not exist in your product/service, you need to build them into your product. Take, for example, Homejoy expanding into all sorts of home services after starting with house cleaning. If the use cases do exist in your product/service, but consumers aren’t using them, you need to invest in awareness or incentivizing a trial of them. For Pinterest, this might be upselling someone who uses the service for recipes to try planning a vacation with the service, or a web Pinner to try the mobile app. For GrubHub, this might be giving a discount for a pizza orderer to order sushi, or a web orderer to try their first mobile order, or a delivery user to try their first pickup order.

These opportunities might not exist or be worth the effort. When I worked at Apartments.com, we knew people would only look for apartments once a year or less. There was not much we could do influence that. What we could do was stretch our product to be useful for not just the apartment search, but also services you need once you find an apartment e.g. moving. Beyond that, there wasn’t much opportunity we could tackle, meaning we’d probably have to spend money to acquire those same users whenever they looked for an apartment again.

Frequent, Non-Loyal Strategy: Incentivize Platform Use

In this segment, consumers are very active, but don’t always use your product/service over a competitor. This is the most common type of loyalty segment because it’s easy to understand the upside. You can typically measure how much activity occurs off your platform. Here, you need to invest in an incentive to move those uses onto your platform. This typically takes the form or rewards points or punch cards.

Frequent, Loyal Strategy: Build Moat

In this segment, consumer are very active and don’t use anyone else for your product/service. These are your best customers. So, a loyalty strategy shifts from trying to increase how often someone use the platform to doing all you can to make sure these consumers don’t decrease their use of your platform or are wooed away by a competitor. This is by definition a money losing strategy to decrease risk instead of a money making strategy in the first two segments. Moat strategies can take many different forms and are frequently misunderstood. Some start out looking like the same strategy as frequent, non-loyal. One common one is to increase switching costs. One example of that is Facebook shutting off friend access to competing apps.

Many other moat building strategies get much more creative. They rely on looking at every possible risk to your consumers doing less of what they’re doing today and trying to address it. One of the most ambitious is Google’s launch of Android. Google makes most of its money from web advertising. They saw consumer attention shifting from an open, web platform they increasingly controlled via their browser Chrome to closed platforms on mobile owned by competitors Microsoft and Apple. So, they acquired and put hundreds of millions of dollars behind their own, open operating system in Android, which they charge no money for, but powers most smartphones all over the world. This is all so they could continue to control how people searched and saw ads in a mobile world.

So, we can go back to that 2×2 with our strategies now.

Now that you understand the segments and their corresponding strategies, you need to identify where the opportunity is for your product or service. The easiest way to do that is to run a survey to determine loyalty, and mine your user data for frequency. Then, see where the highest percentage of your users are.

This post covered how to identify which segment to focus on and the appropriate strategy to pursue. My next post will talk about making that strategy and implementation successful.

Having worked in marketing for almost a decade now, I have seen a lot of change. One of the most fascinating is the change of what people around me think marketing is and what it is not. To establish the baseline of how I think of it, and how marketers typically think of it, it helps to look at the official definition from the American Marketing Association:

Marketing is the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large. Source.

Since that’s a mouthful, marketers tend to shorthand with a series of P’s (four to seven depending on who you ask). For products, those are product (the creating part of the definition), price (the exchanging part of the definition) , promotion (the communicating part of the definition), place (the delivering part of the definition), positioning (the value part of the definition), people (the people who do the activity), and packaging (another part of the communicating piece of the definition). For services, those are product, price, promotion, place, people, process, and physical evidence. These are consistent with how I was taught in my marketing undergraduate classes as well as those in my MBA.

If you visit that link above, you’ll notice the AMA also goes through the trouble of defining marketing research on the same page:

Marketing research is the function that links the consumer, customer, and public to the marketer through information–information used to identify and define marketing opportunities and problems; generate, refine, and evaluate marketing actions; monitor marketing performance; and improve understanding of marketing as a process. Marketing research specifies the information required to address these issues, designs the method for collecting information, manages and implements the data collection process, analyzes the results, and communicates the findings and their implications.

I’ll come back to research, but first, if schools are teaching what marketing is consistently, is this how marketing is being defined in the marketplace? At least in the tech industry where I’ve spent my entire career, increasingly no. Let’s break down some of these functions.

Product

This is the process of creating something of value for customers. This is almost always its own organization lately, and with varying degrees of interaction with marketing. In technology companies, product managers are more likely to have engineering backgrounds than marketing backgrounds. I myself am a part of the Product org at Pinterest (though I was in the marketing org at every other company).

Price

This is the process of determining the willingness to pay of different consumer segments, and setting a price that is attractive to the segments that are attractive to the company. Who owns this very much depends on the org. I have seen pricing owned by finance and sales more than marketing in my career.

Place

Place is where the product/service is sold. In technology, the internet is the prominent place, and determining whether an app strategy makes sense is the key question people need to answer regarding place. Sometimes a marketing decision, sometimes a separate product org’s decision. For sales-driven companies, this is frequently owned by the sales org.

Promotion

This is the act of making potential customers aware of and driving purchase of the product/service. Even in promotion, marketing functions are being splintered through multiple departments. PR is sometimes its own separate department. Many of the more direct marketing channels for technology companies (SEO, email, notifications, viral loops, conversion optimization) are unbundled into a separate product and engineering team typically called “growth”. Marketing still mostly has a stronghold on events, campaigns, and community management.

Positioning

Positioning is the strategy of how a product is presented to potential customers. Many people refer to this as brand, but positioning includes functions of determining a market segment and deciding on a value proposition for that segment. Much of that can and should occur before a product is built. Positioning is about why a company exists and what is stands for. Much of this is still owned by marketing, but I have seen many companies independently position their product and create core values that do not reflect the positioning. This makes it hard to align market expectations with internal processes, and brands suffer as a result.

Packaging

Packaging is the “coat of paint” that defines how a product is presented physically. It is every visual element of your product. This piece has mostly remained a marketing function, though I have seen separate design teams own this before.

People

This term has largely been replaced by the phrase “culture fit” in companies I have worked for, and is measured either by individual hiring managers or by HR or recruiting teams. As a result, this test has represented less about whether this person is a good reflection of our positioning to our customers and more about how well they will work with others internally, creating diversity problems.

Processes

These are the systems developed to deliver on positioning as someone experiences a service, like the line at a Chipotle or someone picking you up when you rent from Enterprise. These are increasingly managed by an Operations team.

Physical Evidence

With a service, there is a lack of tangibility to it, making it hard to value. Physical evidence re-inserts something physical into a less tangible experience to either create a memory or create an easier way for a customer to evaluate a service. This can be something out of the ordinary like a pink mustache with Lyft or a chocolate under your pillow at a hotel.

Now, let’s look at marketing research. In this case, I’ll discuss two newer disciplines encroaching on marketing’s stranglehold of these responsibilities.

User Experience

User experience teams frequently include their own research functions that do qualitative and quantitative analysis to identify problems and opportunities. Qualitatively, this occurs through one on one interviews or by monitoring individual product usage. Qualitatively, this occurs through surveys.

Marketing Performance Analysis

Data science or analytics teams have started to handle more of the monitoring of performance of product usage or marketing campaigns’ impact on growth. The rise of big data has made these processes require specialized statistical as well as technical skills.

Why is this unbundling happening?

I wish I had a stronger theory as to why this unbundling is occurring. Perhaps it is a reaction to years of abuse by advertising agencies and CPG companies trying to get us to buy cigarettes and saturated fats casting an evil stigma around the term marketing. Perhaps it is the technical founder re-imagining these skills with engineers at the core instead of MBA’s. Whatever the cause, marketing is being attacked on all sides, which has the result of redefining marketing with only the least impactful and measurable components, casting further doubt on the value of marketing.

What do we lose with unbundling?

I think the main thing one should worry about is whether an unbundled marketing structure or a bundled marketing structure is more effective, or at least knowing the trade-offs. The main issue that seems to occur with unbundling is that these separate functions lack a shared raison d’etre. Ways I have seen this manifest on the direct marketing side are growth experiments that violate brand guidelines, or a bias toward quantitative research when qualitative research may provide more insight. With operations, I have started to see as this moves further away from separate brand teams, efficiency trumps experience, and trade off discussions between those two things happen less often than they should.

The main issue with a bundled marketing organization is one of management. While the team is more likely to be aligned under one goal and set of rules, there are few if any people capable of managing a department with this large a scope that can have enough of an understanding of these functions to be valuable managers. This is both a failure of educational institutions to teach the “doing” element of marketing instead of just the strategy, a lack of on-the-job training to broaden employees’ view of the organization, and increasing complexity in performing all of the above actions. In this type of org, I foresee the strategy being great, but the execution being terrible because the strategy lacks an understanding of how execution really works.

Where do we go from here?

As I look through this analysis, I can’t help but feel conflicted. While I believe in the definition of marketing and experience some of the pains of these functions growing less and less aligned, I don’t see a rebundling fixing more problems than it creates in these organizations. So I can only hope that this post showcases the value of all of these elements working together, and that people working in these specialized roles start to take a broader view of what’s going on in the rest of the organization, start partnering more with these other teams, and create a better experience for the customer.

What do you think about the unbundling of marketing? How do you think we should react to it?

Thanks to Katie Garlinghouse for reading an early draft of this blog post.

One of my favorite quotes is from Mitch Hedberg:

An escalator can never break — it can only become stairs. You would never see an “Escalator Temporarily Out Of Order” sign, just “Escalator Temporarily Stairs. Sorry for the convenience”. We apologize for the fact that you can still get up there.

I’m reminded of this quote whenever I travel because so many apps on my phone don’t fail over this gracefully. My favorite historically have been foursquare’s. Whenever it couldn’t tell where I was, it would say “A surprising new error has occured.” or “must provide il or bounds”. Let’s forget for a second that these are the most unhelpful error messages ever and get to the bigger problem. foursquare (and most other apps) are designed only for a fully connected, localized experience. This is in a world where, even in cities, 4G connections can be intermittent, and GPS quality is sketchy at best, especially inside. Apps break all the time because of these issues, and it’s not excusable.

As we move towards always in the cloud, total internet and GPS reliant services, software makers need to think about these alternate states and design better experiences for them. It will be a long time before a wireless connection is reliable anywhere in the US, let alone internationally. It will be a while before GPS tracking works well in many places. Connections may be slow. Batteries may be low. Available storage my be low. I like to think of it like testing for different browsers and devices. If you aren’t testing for different connection states or with/without certain pieces of key information, you’re not testing right.

Many have opined about Facebook’s two major strategies over the last couple of years. The first is their aggressive stance on acquisitions, a 180 from their acquihire only approach pre-IPO. This includes Instagram, WhatsApp, Moves, and the real outlier Oculus. The second and more recent is their unbundling of core functionality from the main Facebook app, as with a standalone Messenger app, a standalone Camera app (now being replaced by Instagram), a standalone ephemeral messaing app (Poke and now soon Slingshot), and a standalone launcher app (the miserable failure Facebook Home). One might think I am against such a strategy due to my previous post criticizing unbundling. What Facebook is attempting is something different though.

It is rare that companies get to a point where they start to pursue a moat strategy. A moat strategy makes sense when a core business is so profitable that the most sensible course of action is to build things around it to protect it instead of trying to increase value of customers or try to attract more customers. Google is a famous example of this with Adwords. Its core business is so successful that it pursues projects like free mobile operating system Android solely focused on protecting distribution of Adwords as the world shifted to mobile, and free web browser Chrome to protect distribution of Adwords on web as Microsoft tried to bundle browser (Internet Explorer) and search (Bing) together.

While an entire company ascending so far to the top that its main course of action is building a moat is rare; it is more common on specific distribution channels. Take, for example, search engine marketing and search engine optimization. Once you ascend to the #1 result for an organic search, a normal marketer might stop there and try to optimize other channels. But savvy search engine marketers are just getting started then. A savvy search marketer knows that a #1 result organically does not guarantee that all clicks go to one’s own domain. There are still nine other organic spots and the paid ads, which may still appear above your result. So hardcore search marketers start working on their next trick, owning more than one spot on the search result.

I pursued this strategy at Homefinder. We would take the #1 ranking for certain keywords like “Fayetteville homes for sale”. Once we achieved this, we would bid highly on Adwords as well to take a second spot on the page. Then, we would work with affiliate marketers to bid below us in Adwords to take the second, third, fourth, etc. spots on the page. If someone clicked on those listings, they would go to a different website (as Google only allows one paid ad per domain). But when someone searched on those domains, they were redirected to Homefinder. By pursuing this strategy, we could own perhaps five or so spots on Google for one search, making the likelihood of someone landing on Homefinder much higher than if we just had the #1 spot and nothing else.

The travel companies like Expedia are the masters of this, with multiple brands ranking on the top of Google that are all owned by the same conglomerate not very differentiated. Almost all travel purchases start with Google, so the travel companies maximize this distribution channel more than any other category. For example, Expedia has Hotwire, Hotels.com, and Trivago. Priceline has Booking.com, Kayak, and Agoda.

You might ask what this has to do with what Facebook is doing. Well, on mobile, Google is actually not the only search engine of note. The App Store and Google Play are just as important to optimize for. App store rankings are largely determined by recent download counts, but Google Play is a bit more sophisticated with many engagement metrics. Facebook currently ranks #1 for free apps on Google Play. Did Facebook stop there? No, it unbundled it’s Messenger app completely, which is now the #5 free app. It purchased Instagram, which is the #4 free app. It tried to buy Snapchat, which is the #6 free app. And it purchased WhatsApp, which is the #14 free app. When you already own the top result, you tried to grab as much of the rest of the top real estate as you can.

If Facebooked buys Pandora in the future, don’t be so shocked. This is not just true on the app search engines though. The home screen of the mobile phone is another limited piece of real estate that is incredibly important. Facebook is likely on the home screen of more mobile users than any other app. But it is still only one app among many one can click on when they pick up their phone. So Facebook is focusing on other app that already have wide home screen distribution. I had Facebook, Instagram, and Moves on my home screen. That means, Facebook had a 3/16 chance every time I opened my phone that they would receive some sort of engagement from me.

When you’re optimizing channels, I encourage you to think about the real estate you own on each one, and how you can own more. It’s an incredibly effective strategy even if you’re not quite at the moat building stage.