When I was a teenager, I told my dad about a friend and his dad and how they had seven businesses. He immediately replied, “And none of them make money.” I thought it was an extremely arrogant thing to say at the time, but later, I realized it might be the smartest piece of advice he ever gave me.

When I joined Grubhub, I quickly noticed the founders were incredibly good at staying focused. They said we were building a product for online ordering for food delivery — and only delivery — not pickup, not delivery of other items, not catering, and that’s all we would do for a long time. I remember thinking, “but there’s so much we could do in [XYZ]!” I was wrong. By staying focused on one thing, we were able to execute technically and operationally extremely well and grow the business both very successfully and efficiently. When we added pickup functionality four years later, it proved not to be a very valuable addition, and hurt our conversion rate on delivery.

If you have product/market fit in a large market, you should be disincentivized to work on anything outside of securing that market for a very long time. There is so much value in securing the market that any work on building new value propositions and new markets is destructive to securing the market you have already validated.

There is an interesting switch in the mindset of a startup that needs to occur when a startup hits product/market fit. This group of people that found product/market fit by creating something new now have to realize they should not work on any new value propositions for years. They now need to work on honing the current product value or getting more people to experience that value. Founders can easily hide from the issues of a startup by working on what they’re good at, and by definition, they’re usually good at creating new products. So that tends to be a founder’s solution to all problems. But it’s frequently destructive.

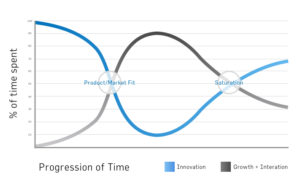

If a product team can work on innovation, iteration, or growth, they need to quickly shift on which of those they prioritize based on key milestones and value to the business. In this scenario, it’s important to define what innovation, iteration, and growth mean. In this context:

- Innovation is defined as creating new value for customers or opening up value to new customers. This is Google creating Gmail.

- Iteration is improving on the value proposition you already provide. This can range from small things like better filters for search results at Grubhub to large initiatives like UberPool. In both cases, they improve on the value proposition the company is already working on (making it easier to find food in the case of Grubhub, and being the most reliable and cheapest way to get from A to B in the case of Uber).

- Growth is defined as anything that attempts to connect more people to the existing value of the service, like increasing a product’s virality or reducing its friction points.

I have graphed the rollercoaster of what that looks like below around the key milestone of product/market fit.

Market Saturation

The time to think about expanding into creating new value propositions or new markets is when you feel the pressure of market saturation. Depending on the size of the market, this may happen quickly or slowly over time. For Grubhub, expansion into new markets made sense after the company went public and had signed up most of the restaurants that performed delivery in the U.S. The only way the company could continue to grow was to expand more into cities that did not have a lot of delivery restaurants by doing the delivery themselves.

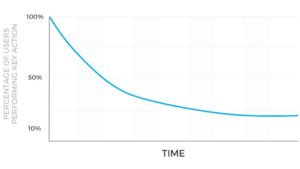

All markets are eventually saturated, and that means all growth will slow unless you create new products or open up new markets. But most entrepreneurs move to doing this too early because it’s how they created the initial value in the company. Timing when to work on iteration and growth and when to work on innovation are very important decisions for founders, and getting it right is the key difference to maximizing value and massively under-performing.