This is part three in a series of posts related to some presentations I did for the TCV Engage Summit. The Summit gathered ~40 CPOs and product leaders to chat through topics centered around product development and product-led growth. This year, topics ranged broadly from incorporating AI to deliver world-class consumer experiences to defining and measuring different forms of community-powered growth. You can read parts 1 and 2 here and here.

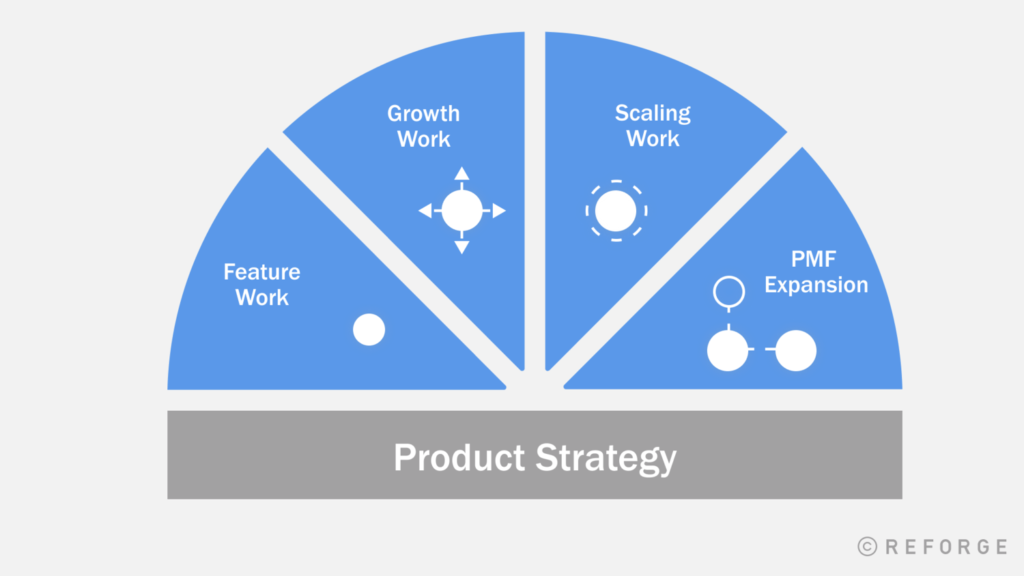

In a previous post, I talked about how product work post-product/market fit shifts from zero to one innovation to features, growth, and scaling work. But a question founders and teams often ask is when do we start layering in innovation work again that creates new value props. In Reforge terms, we call this new product expansion. I recently did a talk for TCV’s Engage Summit where I explained the different types of product expansion, when to start building that second product with a new value prop, and how to know if it’s successful.

Why Second Products Matter So Much

Why do we even care about second products? Don’t some of the best companies in the world win with one dominant product? Well, increasingly that’s not the case. Companies can rarely ride one product into the IPO sunset anymore. Yes, the headlines are filled with many of these examples, such as Google in the 2000s or Zoom in the 2010s, but these examples reflect an environment that is becoming increasingly rare. The tech IPO narrative used to reflect stories that would include much of the below:

- Large markets

- Low or stagnant competition

- Rapidly growing markets

- Strong network effects or economies of scale

- Scarce talent pools

A lot of those bullets can be explained by just the growth of the internet, and there being no entrenched internet-first competition. The maturity of the internet means most of these are no longer the case. Almost every recent tech IPO is multi-product at time of IPO, and the dynamics of their markets appear much different:

- International competition

- Multiple startups in the same space

- Incumbents are tech native, no longer asleep, and copy what works from startups quickly

- There is talent across a wide range of companies and skills

- Network effects are no longer impenetrable

Uber, Instacart, Doordash, Unity, Klaviyo, Nubank, Toast and many other recent IPOs all reflect this new reality.

The Types of New Product Expansion

There are many ways for a company to expand its product offering, with different levels of difficulty. The main vectors on which product expansion should be evaluated is whether the expansion changes the product, changes the target market, or changes the core competencies required to deliver the product’s value. I highlight six different types of product expansion, in increasing levels of difficulty based on these vectors.

| Expansion Type |

Product |

Market |

Core Competency |

Examples |

| Geography |

Existing |

New |

Existing |

Grubhub LA, Pinterest Brazil |

| Category |

Existing |

New |

Existing |

Whatnot Sneakers, Thumbtack Home |

| Format |

Existing |

Existing |

New |

Netflix Streaming, Snap Spectacles |

| New Value Prop |

New |

Existing |

Existing |

Uber Eats, Hubspot Sales |

| Platform |

Existing |

Mixed |

New |

Shopify App Store, Salesforce App Exchange |

| Strategic Diversification |

New |

New |

Existing |

AWS, Cash App |

Geographic and category expansion skills are fairly well developed in software businesses. Companies build a deep understanding of how they achieved product/market fit in the first market, and make as few tweaks as possible to adapt the product/market fit to these adjacent audiences. Most marketplaces and social networks have executed these playbooks fairly well.

Format changes are usually only required around platform shifts already occurring or platform shifts a larger company is trying to drive. The last large one was mobile, and most internet companies were able to replicate their success in mobile. Netflix and Snap have worked on more interesting format shifts, building on entirely new technologies to deliver their value props on new forms of media.

New value propositions are what we traditionally think of for second products, and will be the focus of the rest of this post. This is creating a new value proposition for your existing audience so that you can acquire, retain, and/or monetize them better. In extremely horizontal products, it may be wiser to launch a platform than build a lot of this new product value yourself, but this requires massive scale to attract external developers, and is very difficult to execute. I have written more about platforms here. Strategic diversification is a much rarer phenomenon where a core competency you have built internally is marketable for an entirely new value prop and audience, like Amazon leveraging its core ecommerce infrastructure to sell to other developers, or Square leveraging its financial expertise in SMBs to launch a consumer fintech product with Cash App.

New Product Value and S-Curve Sequencing

In my previous post, I talked about S-Curves. In that post, I mentioned that sequencing from an original S-Curve to a next S-Curve is the key to long term sustainable growth. That sequence can come from finding a new growth loop, but eventually that next S-Curve will require new product value to be created. This is what I realized when I joined Eventbrite. Eventbrite initially found this success with a content loop around event creation.

To continue its growth, instead of investing in new product value, Eventbrite kept grafting new growth loops onto this core loop to acquire more event creators and drive more ticket sales per event, creating a much more complicated growth model that looks like the below.

What became clear after building this model of how Eventbrite grows is that all of this effort would no longer drive the kind of growth Eventbrite needed to be successful on the public markets. We could no longer acquire event creators and ticket buyers fast enough, and we didn’t make enough money from them when we did. If we wanted to grow sustainably, we needed new products. And we probably needed them yesterday. It’s not that the company hadn’t ever tried to invest in new value props, but those that could create significant new growth had eluded them.

When To Invest in New Products

If you want to be proactive in thinking about when you should invest in building new products vs. diagnosing a growth problem and determining new product development requiring years of effort to be the solution, how do you do that? Well, the first step is tracking what impacts the need for a second product inside your company. Besides building a growth model and forecasting your growth from it, which I absolutely recommend you should do, what are the factors that contribute to how quickly you need to be investing in that second product after the first product finds product/market fit?

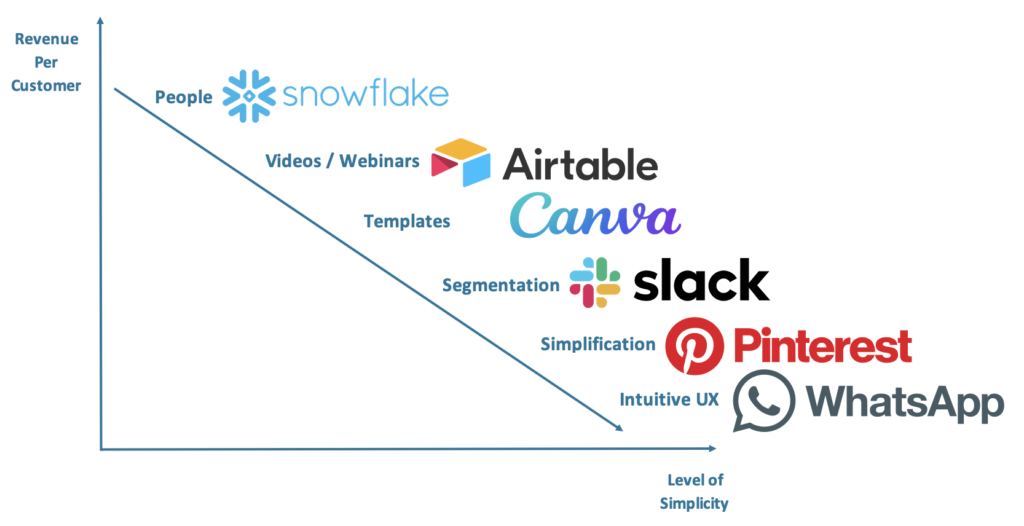

Historically, the factor that most people use as a heuristic is the business model. Traditionally consumer businesses have longer S-curves, so there is less of a need for a new product to drive growth. B2B requires suite expansion. Why does B2B require suite expansion? Well, they usually do not have network effects which makes marginal growth harder, of course, but the main reason is competition from bundled competitors. Acquisition, retention, and monetization potential of your first product is another reason B2B tends to expand earlier. Second products influence sales efficiency and profitability dramatically. Next is the size and growth of the market. If the market is large, your product can grow inside it for a long time. And if the market is growing fast, market growth can frequently drive enough company growth on its own, like, say, Shopify with ecommerce. The smaller the market is, the faster you need to expand the addressable market to grow. The last factor is how natural product adjacencies are for your first product. Generally, in B2B, product adjacencies are more obvious and less of a gamble to invest in. Launching successful consumer products is very hard with a very high failure rate.

But I’m going to show you why if you pay close attention to these other factors, the business model can be a red herring.

New Product Expansion by Business Model

Let’s break some examples down by business model and start with pure consumer businesses. Pinterest and Snapchat were compared a lot because we started scaling at around the same time. And even though they are both the same business model, you can see some of their attributes look a lot different.

First, no one actively competed with Pinterest during its rise to be the primary way people discovered new content related to their interests. Snap, meanwhile faced an aggressive competitive response from Instagram as they grew to be a place where friends interacted around pictures. From a customer acquisition perspective, the companies grew in very different ways too. Pinterest grew by capturing users searching for things related to their interests on Google while Snapchat grew virally. Their retention strategies were also different. Pinterest primarily increased engagement by learning more about what you liked and recommending content better and better matched to your interests over time. This is usually a strong retention loop. Snapchat built out your friend graph, but didn’t really get much stronger after that. In fact, too many friends might be off putting. The most important difference was the monetization potential. Pinterest’s feed of content related to your interests is a perfect model for integrating advertising and commerce, the two best consumer business models. Disappearing photos however was not a good fit for either of those models, and likely best lent itself to subscriptions and virtual goods, both largely unproven at consumer internet scale. Lastly, Pinterest grew adjacencies by making the product work better with interests in different local geos and in different categories e.g. travel vs. fashion. Snap had similar geographic growth, but had some additional format and product adjacencies.

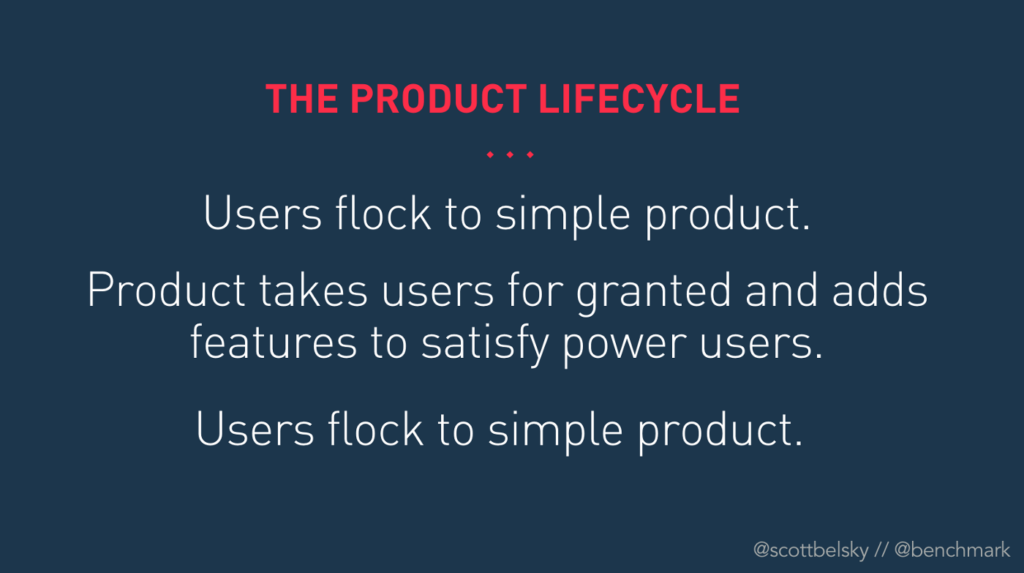

Okay, so let’s look at how Pinterest and Snapchat grew their product offering over time. We’ll focus on the consumer, not advertiser side of the equation for this example, though obviously both companies built advertising products. The companies launched around the same time, and launched their second products around the same time. Pinterest significantly evolved how its core product worked, changing both the acquisition and retention loops over time. Acquisition shifted from a content loop built on top of Facebook’s open graph to a content loop built on top of Google with SEO. The way Pinterest retained users also changed, from seeing what your friends were saving to getting recommended the best content related to your interests regardless of who saved it. Snapchat did not evolve their core product nearly as much. But Snapchat’s second product was a lot more successful. Snapchat Stories was a huge hit. Pinterest around the same time released Place Pins, a map based product that did not find product/market fit and was deprecated. Both companies also launched additional new products in the coming years. Snapchat found new product success again with Discover, and Pinterest again failed building a Q&A product around saved content.

So wait a minute? You’re telling me Snap succeeded multiple times in product expansion where Pinterest failed, yet the companies are valued at about the same. What gives? Well, it turns out Pinterest didn’t need to expand into new products because its initial product had great acquisition, retention, and monetization potential, albeit with some evolution on how they worked. Iterating on its initial value prop was the unlock, not creating new value props. In fact, the new product expansion work outside of expanding countries and categories was a distraction that probably prevented the core product from growing faster. The company might be worth double if it had not spent so much time trying to develop new products. Snap, however, probably would not have survived without product innovation because its first product had low monetization potential. They needed those new products to work, and they did.

Let’s look at an example in SaaS. I had the pleasure of working with both Figma and Canva as they were developing. I was an advisor to Canva starting in 2017, and got to work with Figma while I was a growth advisor at Greylock, which led the series A investment. It’s a fascinating example of two design tools targeting entirely different audiences, basically designers and non-designers.

At the time of their launch, Figma was in a competitive space with legacy products from Adobe, and many tech companies were using Sketch. Theoretically, Adobe’s Photoshop was the competitor for Canva, but it was much too complicated for laypeople to use, and much of Canva’s pitch was that it was Photoshop “for the rest of us”. Both could acquire users by having creators share their designs. Figma looked like it would be a much higher retention product as it was multi-player from the start, and applicable to larger businesses. Canva was more of a single player and SMB tool. As a result of this, it looked like Figma would monetize a lot better, with a classic per seat model selling to enterprises, with Canva having a lot of single user subscriptions.

At the time, investors didn’t think the design market was one of the larger markets out there (they were wrong), but everyone did think the category was high growth. Both companies had some nice theoretical adjacencies in terms of formats they could work in, new products they could create, and platform potential.

Both companies evolved how they acquired users over time, layering in sales, and Canva got a huge boost from SEO. Both companies also evolved their retention strategies. Figma became a tool not just designers to collaborate, but for those designers to collaborate with their peers in engineering and product. Canva created lots of ways for users to not start from scratch with community-provided templates and stock photos to leverage.

Figma launched its first new product in 2019, called Figma Community. It intended to create a Github-like product for designers, or perhaps a Dribbble competitor. It has not reached the company’s expectations. Canva launched Presentations in 2021, and it has become a heavily used product. Both companies have continued to invest in delivering new value props. Figma launched Figjam, a Miro competitor in 2021. It has not become the Miro killer the company imagined as of yet. Canva launched its video product also in 2021, and it continues to gain traction, along with a suite of other enterprise bundle features more recently, like a document editor.

So on paper, it looks like Figma’s in a competitive space. Canva is not in a competitive space. But while Figma has had mediocre product expansion and is still being sold for potentially $20 billion, Canva is grinding on building out a suite to succeed. Why? Because Figma’s product/market fit so quickly surpassed what was on the market that products ceased to become competitive over time. And while Canva didn’t have competitors, it became a substitute to the big incumbents Adobe and Microsoft, forcing them to build copycats and respond. Canva as a point solution likely loses out to their bundles if they don’t expand their suite successfully.

Time and time again, we see two things. One, companies in the same space may need to think about new value prop development much earlier than other seemingly similar companies. Two, we see new products not inflect company growth when they are a random bet on innovation. New products tend to work when they have to work for the company to succeed. If you can still grow your core product, they rarely get the focus they need to succeed, and furthermore, might be a less efficient use of resources than continuing to grow the core business. Figma will not live or die on the success or failure of Figjam. Canva might need these new products to be successful to stay competitive long-term.

Portfolio approaches that recommend some percentage of development on innovation vs. features vs. growth vs. scaling tend not to be where massively successful second products come from. Understanding your growth model, and betting big on new product development when you sense the company needs it, tends to be the more successful approach.

Okay, let’s look at a marketplace example. Here is where you see how marketplace strategy has needed to evolve over time. Older marketplaces like Grubhub were extremely profitable because they did not facilitate the transaction beyond payments. More recent startups like Instacart have needed to manage a significant component of the delivery of the value prop, which means its monetization potential out of the gate is much worse.

Similar to Snap vs. Pinterest, Grubhub’s initial market was so large and so profitable that all new product value expansion did was limit the potential of the core product. Pickup cannibalized search results and lowered activation rates, especially in some key markets like LA that allowed upstarts to gain traction, notably Postmates.

Instacart’s initial product however required so many complex operations that it found it could not eke out real profits while paying groceries and pickers. But it could expand its network to CPG advertisers, replicating grocery market slotting fees in a digital product. So these companies had very different paths to similar market caps despite both being labeled marketplaces.

Last, but not least, let’s look at a consumer subscription example. Duolingo and Calm launched around the same time as consumer subscription apps. Both are in competitive spaces that struggle with retention because building new habits is hard for consumers. The language market is however considerably larger than meditation.

Both companies evolved their acquisition strategy over time, but Duolingo got a lot more leverage out of virality, keeping their acquisition costs much lower. Duolingo’s core product experience also got stronger over time through both data and manual improvement in lessons from user engagement, and laying in gamification tactics. Calm moved from web to app, and built in some daily habits that helped retention.

What made Calm a much more interesting business though was the launch of Sleep Stories. Not only does expanding into sleep expand the target audience dramatically, it makes it easier for Calm to become attached to a durable habit. People have to sleep; they don’t have to meditate. Calm also was able to expand into B2B by selling Calm as a mental health benefit. Duolingo did not have the same success in new product expansion. While the core product continued to get better at covering more languages, new product efforts failed to create value, such as TinyCards in 2017. Yet, even with this fact, Duolingo appears to be a lot more successful than Calm, likely primarily due to the acquisition strategy and larger initial target market.

In these scenarios, it is not good to assume you are one of these companies on the left side of the table where your initial product/market fit will have such a large addressable market and lack of competition that you can scale successfully without new product development. It is also dangerous to assume you will need a lot of new product innovation when your initial target market ends up being quite large. What I urge companies to do is dig deeper into the attributes in these tables for their company, and re-ask these questions every year as we have seen many of these market dynamics shift dramatically over time.

How to Know If New Products Are Successful

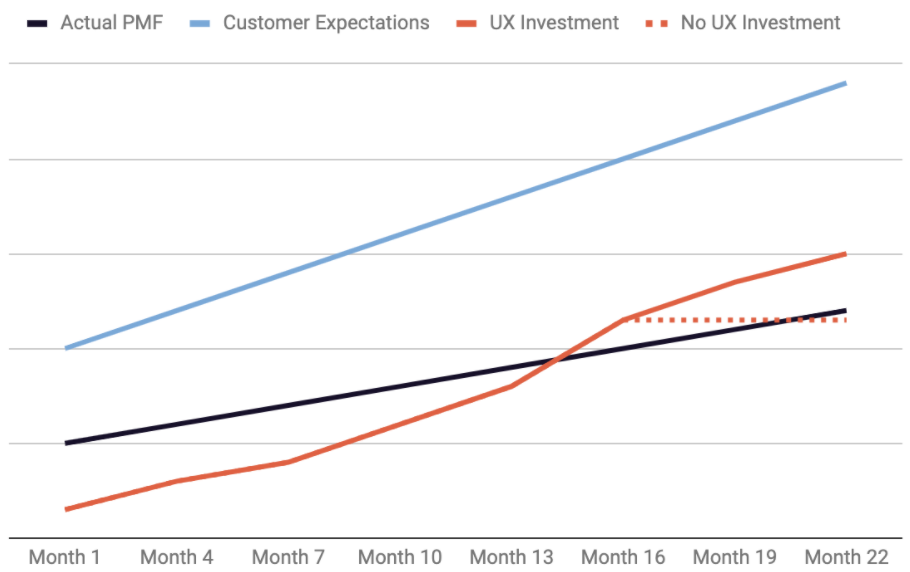

So when is a new product “successful”? Well, the answer, surprisingly, is not product/market fit. If you’ve read some of my work, you know I define product/market fit as satisfaction, normally measured by a healthy retention curve, that is through its own engagement or monetization able to create sustainable growth in new users for a significant period of time.

But second products don’t need to do all of that to matter. Whereas a new startup isn’t going anywhere unless it figures out acquisition and retention (and maybe even today monetization), new products may only need to influence one of the three to be successful. But the key is, they need to influence it for the overall company, not just the product itself. So if a second product has high retention and can effectively acquire new users, but can never inflect the growth of the overall business, it’s not successful.

This is why developing a growth model above becomes so important. It can tell you if the new product is developing fast enough to inflect growth of the overall business, and when that might happen. And if it isn’t, you can understand what it will take for that to happen. This is something that confuses product teams that work on new products inside larger companies. By the frameworks they understand, the new product “is working.” It has product/market fit, it’s growing, etc., but it can never grow enough to really help the overall company.

–

Most companies struggle to understand when they need to start investing in adding new product value vs. just continuing to grow off the traction of their initial product/market fit. But it is becoming necessary earlier and earlier in a company’s lifecycle due to a confluence of factors. In order for us to get better at building great, enduring businesses, we need to talk about the types of expansions that matter for companies, and assess at an individual company level what is required for the new phase of growth. Modeling your growth really is a helpful start, and digging deep into understanding the competitive landscape, the acquisition, retention, and monetization potential of your current business, the size and growth of your market, and what your natural adjacencies is becoming critical to make the right calls at the right time regarding new product investment. New products work when they have to. It’s time to ditch outdated portfolio practices and innovation teams, and build modern approaches around when to start building, investing hard in building new products when it is the right time, and evaluating their success or failure properly.

Currently listening to my Early Dubstep playlist.