If you’ve been following the online food delivery space, now is a pretty exciting time. Multiple services are starting up, competing on different value propositions, and many corporations are theoretically launching businesses here as well. There is one clear giant, and it is unclear if any of the upstarts will challenge them. But what is so interesting is how large companies entering the space and new startups alike are confronting the different value trade offs in online food delivery. I’ll first describe the different types of services, their different components, and then their trade offs.

Types of Services

Marketplaces

Services: GrubHub, Seamless, Eat24

Marketplaces aggregates delivery restaurants and allow diners to search for restaurants that deliver to them. The restaurants do their own delivery.

Delivery Services

Services: Postmates, DoorDash, Caviar, Uber Eats

Delivery services offer delivery from restaurants that don’t do their own delivery and deliver the food themselves.

Delivery Only Restaurants

Services: Sprig, Spoonrocket, Maple

Delivery only restaurants have no storefront. They just make food that is available for delivery and deliver the food themselves.

Delivery Only Restaurants that Require Prep

Services: Munchery, Gobble

These restaurant services require some prep work ranging from microwave to stove or oven, but usually it’s only a few minutes of prep required.

Delivery of Ingredients/Recipe Only

Services: Blue Apron, Plated

These services deliver the ingredients and the recipe required to make a meal, but the diner has to cook it themselves.

Delivery of Groceries

Services: Instacart, Fresh Direct

These services deliver whatever items you want from a grocery store.

I won’t go into corporate focused services in this post.

Value Propositions

Variety

People rarely agree on what food they like, let alone on which food they want to eat at a specific time. While GrubHub is currently unmatched in its variety nationally with over 35,000 restaurants, different companies are tackling variety on both sides of the spectrum. Postmates will theoretically offer the most variety as it will pick up food from any establishment. Online food companies like Sprig, Munchery, and Spoonrocket limit options considerably each day. Doordash, Uber Eats and Caviar have the most confusing approach here, as their ability to use their own delivery network does not restrict them to restaurants who already offer delivery, but they curate the list to provide supposedly only great options. GrubHub works with every restaurant that does delivery already, and has expanded the market by convincing many restaurants to start delivery because they see how well other restaurants do by offering that option with GrubHub.

Prep

Convenience has two components: how much work you have to do to eat (prep), and how quickly the food arrives (time). Marketplaces, delivery only restaurants and delivery services deliver ready-to-eat food. Then, there are some that require a little prep, some that require full cooking, and some that require figuring out what to cook and cooking it.

Time

The other convenience layer is time. Delivery only restaurants target 10 minute delivery times by pre-pepping meals and loading them into the cars of their drivers, whereas GrubHub and Eat24 are closer to 45 minutes to an hour depending on the restaurant’s location and type of food. Delivery services tend to take over an hour as they require extra coordination with restaurants. I believe Uber Eats is attempting a hybrid of the delivery service model and the delivery only restaurant model, but I can’t confirm. None of the other services deliver food ready to eat, but they range on how much work is required. The some prep restaurants are more like 10 minutes to heat, and ingredient/recipe services require typically cook time of over 30 minutes to an hour.

Price

Price varies for all of these services. Delivery only restaurants target less than $15 everything included. While that is possible in some cities with marketplaces, it is not in others. Ingredient/recipe delivery services have plans that are under $10 per person. Delivery services tend to charge a fee for delivery or mark up restaurant prices, so they are typically more at $20 and above per person. This incentivizes group order to spread the delivery cost around to multiple people. This is why most delivery services end up focusing on corporate catering instead of consumers over time. Prep delivery only restaurants have different plans to entice regular ordering.

Quality

In marketplaces, the quality options are set by the market, and the diner chooses how good they want their food to be. Delivery services have the same option with perhaps a higher end than marketplaces as the very best restaurants tend not to deliver. The delivery only restaurants tend to be cheap and low quality so far. Whether you had a hand in making it yourself can also be considered a quality parameter, as some people to tend to prefer things they cook themselves.

Planning

With food delivery, one typically does not need to plan in advance to use it, but with new grocery delivery and ingredient/recipe prep services, diners need to plan ahead of time to use the service.

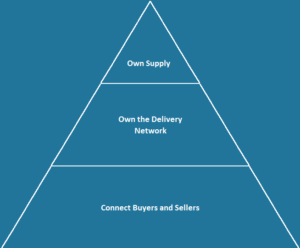

Trade Offs

As you start playing with these value propositions, you recognize some additional constraints. I don’t need to lecture you in price vs. quality. That’s pretty obvious. But what may not be obvious is the trade off between time and quality. Even if you are delivering food from an amazing restaurant, if it takes a long time to get to a diner, it’s typically not very amazing by the time it gets there due to the food being cold. The other interesting trade off is quality vs. variety. At GrubHub, our stance was akin to the saying “quantity is a quality all its own.” In that, if you organized all of the supply, even if you had many amazing restaurants and many not so good ones, the good ones quickly emerged to the top due to ratings and reviews and overall quality of the service improved. So, all GrubHub worried about was variety and convenience, with convenience mostly limited to the ordering and customer service experience. Price and quality were set by the market, but presumably, variety solved quality, with a cap on the high end.

What these new services are doing is taking constants in the marketplace equation and making them variables: prep, time, price, and quality. It is way too early to tell if changing the equation is valuable to the broader market as GrubHub does way more orders in a day than the rest of these services combined. But it will be interesting to watch.