With Black Friday this year, I thought I’d see what I could pick up for myself online with the deep discounting going on. Shopping online was a breeze. I could do it at my own pace, search exactly for what I wanted, and not have to deal with any crowds. Why anyone is camping out in front of stores for this day I’ll never understand.

Unfortunately for brands, marketers seem to be getting just as irrational as the bargain shoppers they’re attempting to exploit. For this blog post, I’ll use Bonobos as an example. I made my first purchase on Bonobos.com over six months ago, after seeing an ad on Facebook.com offering $50 off my first purchase. Bonobos is known for making pants that fit the American male better than European designers. When I browsed the site, I noticed that even with $50 off, the pants were still too expensive for my liking. As a result, I purchased some shirts with my discount. Since then, I have been back to the site a few times to see if their prices have lowered, and they never have.

Bonobos has used an advertising device called retargeting aggressively since that point in time. What retargeting does is identify someone like me who has come to a website, but did not buy. Then, wherever else I go on the internet, Bonobos will attempt to show me ads. In this case, they show a discount of some sort to entice me to return. It is a good strategy, but it has never worked because the prices are still too high.

On Black Friday, browsing another site, I see a retargeting ad for Bonobos promising 20% off. It is more aggressive than what they offered previously, so I click on it. When I arrive at Bonobos, I see a message about their Black Friday deals, which are $15 off a $100 order, $40 of a $200 order, and $150 off a $500 order. To compare directly to the retargeting ad, these discounts are 15%, 20% and 30% respectively. I browse the selection, and it’s still too expensive for my tastes. I leave the site, and browse the web a little more. While on Twitter, I see someone I follow recommend Fab.com. Fab sells all sorts of design products at deep discounts for limited periods of time.

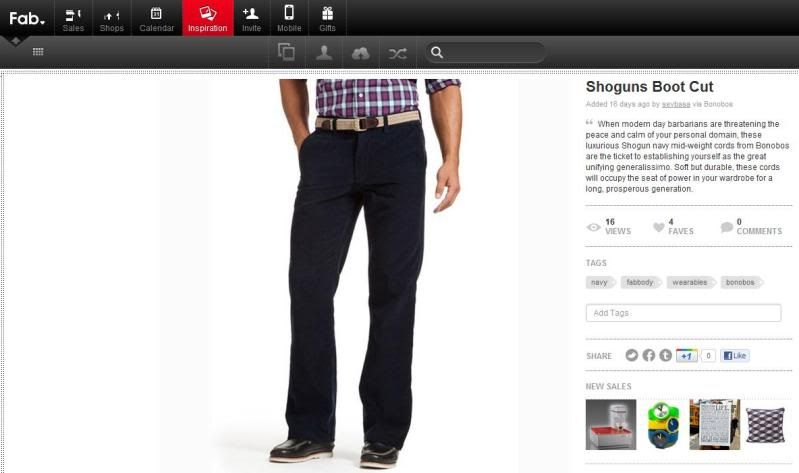

Designers will let Fab sell their items at a discount to build awareness of their brand among their vast email list and to relieve themselves of unsold inventory. This makes sense, as the cost of production is a sunk cost, and any price you can receive for these goods is better than having them take up space in a warehouse. I had heard of this site before, and thought it might have some solid deals for Black Friday, so I sign up. As I scroll down the page, I notice a deal for Bonobos, which is 40% a select group of items. This brings their prices down to an affordable level for me. Fab had my size, so I purchased some pants.

These same items were available on Bonobos.com, but for about double the price. I wondered why Bonobos would be willing to let another site charge a lower price, in which case Fab collects all of the customer information, so Bonobos does not begin to develop a personal relationship with the customer. They’re likely also making drastically less from Fab than through a direct buy on their site.

I think, in this case, Bonobos was operating under an assumption that if they insert a third party between this lower price and their brand, it would not harm their ability to charge more in normal cases than if they advertised these prices on their own website. I also think they might have been trying to lure new customers from Fab. They are able to brand these prices as from Fab, and not from Bonobos.

I wonder if this is the right strategy or a sophisticated form of mental accounting. In this case, they were willing to offer a known customer like me less of a deal for going direct than through going through a third party where they have to pay Fab a part of the sale. Bonobos would have made more revenue by showing these prices directly on their website, and would also have been more likely to make the sale. They are lucky I saw this deal on Fab. They almost lost a sale on inventory which they are desperate to rid of.

Disregarding Fab entirely, I also did not understand why the retargeting ad and the Black Friday deals on Bonobos.com advertised such different promotions. One could make the argument they were testing which offers were more impactful. This type of test is much easier to do with A/B testing. Furthermore, if you are testing, you would want to complete that test well in advance of a big event like Black Friday so you know you are using the promotion which is most impactful. It appears Bonobos is advertising irrationally, using mental accounting to justify different offers in different advertising locations, even though, in many cases, they are reaching the same potential customer and just confusing them. There should be no reason they are willing to spend 40% to drive a sale on Fab, and anywhere from 15%-30% based in volume or 20% via retargeting for, in many cases, the same merchandise.

I feel guilty for beating up on Bonobos because they’re a good company, and their site went down for Cyber Monday, but hopefully they learn to present a consistent promotional strategy that aligns with their goals and their profit margins.

The reason Bonobos offered steep discounts through Fab was that the items and styles on Fab were unpopular ones. That’s my guess, at least, having looked at the sale items on Fab; they seemed to be long out of season and available only in uncommon colors and sizes (XL, bootcut, etc.). Bonobos, I presume, sold overstock to Fab in the hope of achieving brand recognition among Fab customers. Gilt does the same thing. Even if Fab users didn’t buy the Bonobos clothing, seeing the Bonobos brand name among other brands they respect (since they respect Fab’s picks) makes them more likely to buy in the future.

Daniel, thanks for your comment. That certainly makes sense. Why not sell these unpopular items on Bonobos.com for the same price though? These same items were much more expensive on Bonobos.com. Is not dicounting on Bonobos.com so Bonobos.com shoppers don’t see lower prices in general? Then perhaps they wouldn’t compare prices between the unpopular and popular items?

The reason may be that they’ve found that customers browsing their products on their site are willing to pay more for a product than customers browsing their products on Feb. This makes sense, since Fab is focused on offering low prices.

Bonobos is effectively price discriminating here, and your experience demonstrates that it works. You saw a price on their site FIRST, didn’t like the price, and didn’t buy. You saw a lower price elsewhere LATER, liked the price, and bought. A less price conscious consumer would have made the first purchase, and Bonobos keeps the price difference — essentially transferring the consumer surplus to themselves.