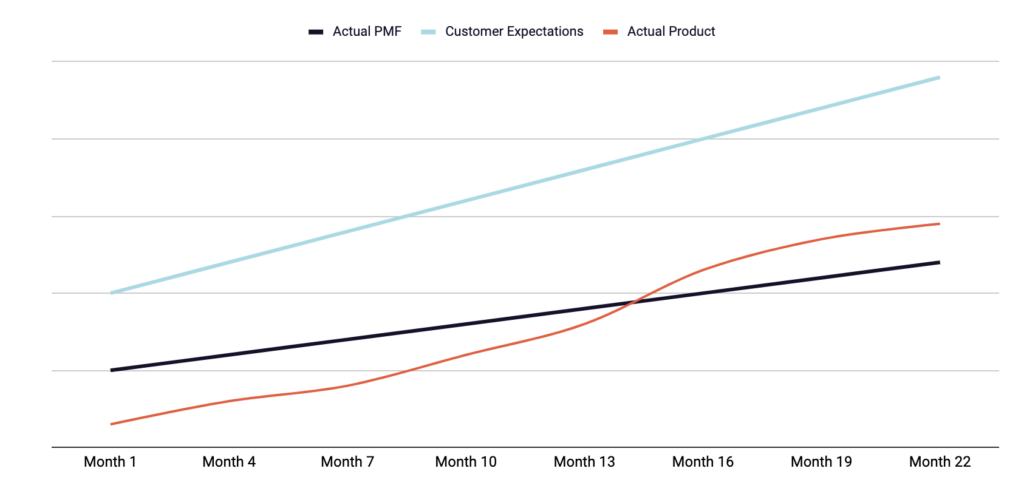

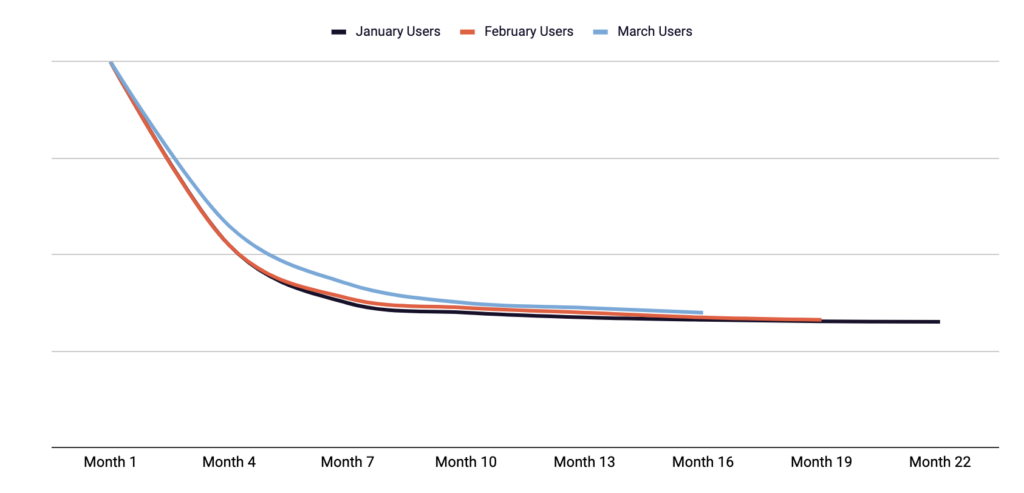

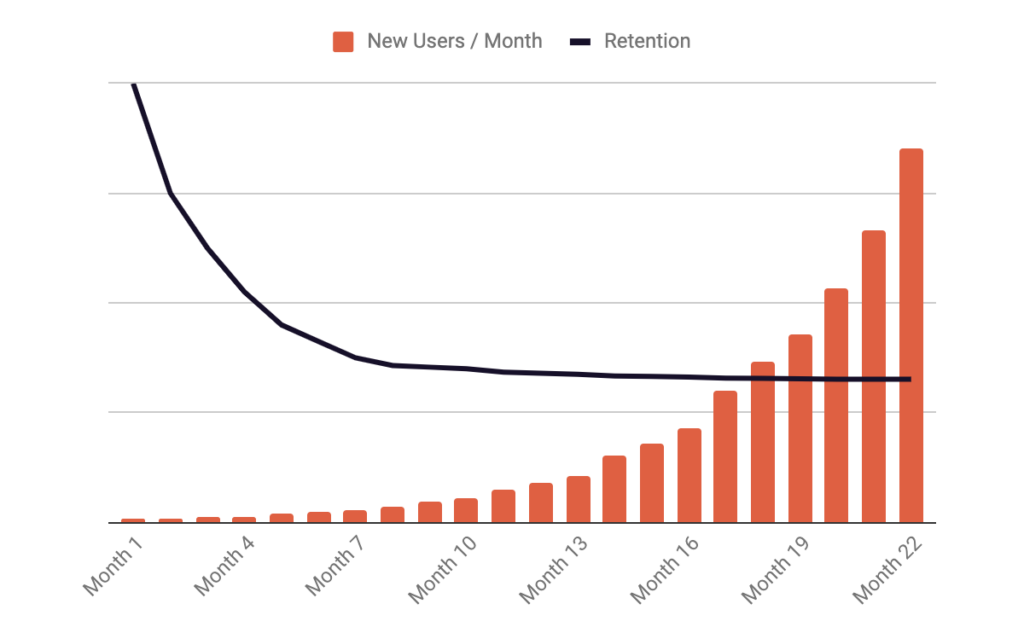

I have written a lot about product/market fit in the past. Whether you are a founder, product or growth leader, being able to recognize and measure product/market fit is a critical tool to make the best decisions on driving success of a company. In the post I linked to above, I make a case on the two metrics you really need to understand about product/market fit: retention and acquisition, and that product/market fit is really about finding a level of satisfaction (usually measured through retention) that will drive scalable acquisition. If you apply this model to a SaaS business, the application is usually pretty straight forward. Measure the retention of your customer, and does either the virality or monetization unlock scalable acquisition loops like sales, performance marketing, referrals, or content. Many founders struggle to apply this same framework for network effect businesses though, and it’s easy to see why. Frankly, it is just much harder. In this post, I’ll break down the nuances of product/market fit for network effects businesses to understand if you’re on the right track.

When a network is a key component of the value prop you are trying to create, and things aren’t going well, it’s hard to understand which is the real issue preventing the product from reaching product/market fit:

- Is the product’s value prop not valuable enough?

- Is there just not enough people or content to make it valuable yet?

- Conversely, could there be too many people or too much content to retain the value?

I’ll break down some additional insights to product/market fit for different types of network effects to make the product/market fit mystery easier.

Cross-Side Network Effects (Marketplaces and Platforms)

Cross-side network effects can be painfully difficult to find product/market fit for because you are building out a product for two different types of customers that have to align. It can feel like building two companies at the same time. Fortunately, there are some easy ways to navigate this puzzle to make the journey to product/market fit less amorphous. The first is that for businesses like marketplaces, it tends to be easy to understand how to constrain the audience initially. The first thing to understand is that there a spectrum of network effects from global to local:

- Global Network Effect: every seller makes the product better for every buyer and vice versa e.g. Ebay, Airbnb

- Local Network Effect: every seller within certain area makes the product better for every buyer within certain area and vice versa e.g. Grubhub, Ritual

Based on whether you are pursuing a global or local network effect, you can usually either constrain the audience by category or geography to start: Grubhub started in one neighborhood in Chicago, for example. Amazon started with just books.

Assuming you pick the correct geographic or categorical limit, you can test the value prop and scaling of supply and demand to find liquidity, which is a synonymous term with product/market fit for marketplaces. There is almost always a quality and quantity element to liquidity. If you understand it, you can then measure product/market fit by just analyzing retention and acquisition for both sides of the market.

Platforms are more complicated in the beginning, but eventually follow the same logic as marketplaces; they are just less likely to have a geographical component at the core. Whereas marketplaces need supply to attract demand and are willing to do unscalable things to generate that initial supply like paying drivers to sit idle for Uber and Lyft or delivering from restaurants who are unaware they are on your platform like Postmates and Doordash, platforms tend to have to be the initial supply themselves. Let’s take a look at a couple of different examples. Nintendo has had some of the most successful hardware platforms in gaming across decades. One of their secret sauces is that they seed supply on their platform with games they build themselves that they guarantee are high quality. Now, they can afford to do that with games that are based on incredibly valued IP like Mario, Zelda, and Pokemon. This creates initial demand for a new hardware platform like, say, the Nintendo Switch, that then attracts third party developers to build games for the platform as well. Then, Nintendo can look at demand side retention through purchases of games, and supply side retention through creation of multiple games. This helped them understand that platforms such as the Wii and the Switch had strong product/market fit, whereas the Wii U and GameCube much less so.

The success of the Nintendo Switch was partially due to the console launching with one of the best reviewed games of all time from a beloved franchise: The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

On the software side, Shopify and WordPress have spent decades building their own SaaS features to allow the platform to become stronger and stronger with other features built by external developers they would never consider in their roadmap. Now, the majority of the value may be generated by third party developers, but a lot of first party development was required to get them far enough along in customer acquisition to make it attractive for so many developers to build on top of their platforms. You can read more about building successful platforms here.

Data Network Effects (Personalization and Recommendations)

For products that expect to create a better experience through data, the journey to product/market fit is usually about collecting enough data to provide a compelling experience. For some products, this takes a massive amount of time. Pinterest, for example, started as more of a tool for individual users to collect cool things from the internet before it could become a real recommendation engine for things related to your interests based on the wisdom of the crowd. Tinder can recommend great matches after just a few swipes. After I joined Pinterest, we had to make a hard pivot to onboard new users based on topics instead of their friend graph as we realized there was stronger product/market fit as a content recommendation engine vs. a social network. This creates an issue for geographical expansion. By default, we would not have enough data to understand local tastes. To rectify this, we had to reconfigure our feeds to emphasize the local content we had, in the local language, and in the local way of measuring (no more imperial measurements!). And in some markets, the focus needed to be gathering content so we could even have enough local content to display.

Direct Network Effects (Communication Tools and Social Networks)

For many network driven businesses, especially in the social realm, there is a Goldilocks zone of user experience. Too few people or content, and there isn’t enough content to consume or people to communicate with. Too many people or too much content, and it becomes overwhelming, or generates too many notifications. When Yogi Berra said, “”Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.”, it’s easy to imagine he was talking about Clubhouse, not a local restaurant at the time.

Clubhouse downloads per month. This graph is not up and to the right.

For a marketplace, there is usually a clear way to constrain the audience to generate appropriate retention metrics to evaluate product / market fit. Geography or category is the dominant mode for this in marketplaces. For SaaS, it’s a specific target audience. But social or content driven networks eventually want to scale to everyone, and a lot of times founders or leaders can’t tell which should be the first audience that will hook onto it. The better your thesis, the easier it is to evaluate e.g. Harvard only with Facebook, midwestern moms with Pinterest, USC with Snapchat. So the dominant strategy for building direct networks effect business is to have a strong thesis for the target market, prepare to be surprised both who the target market and right features are, and shift to another type of network effect over time. Outside of communication tools, it’s usually my belief that direct network effect products are actually cross-side network effects products where it’s just too early to understand who the different sides are. So, founders have to understand the user data or have a strong vision for what type of cross-side network effect or data network effect can be created to scale product/market fit over time. Do this, or risk becoming like a lot of other flash in the pan social network fads that failed to scale.

–

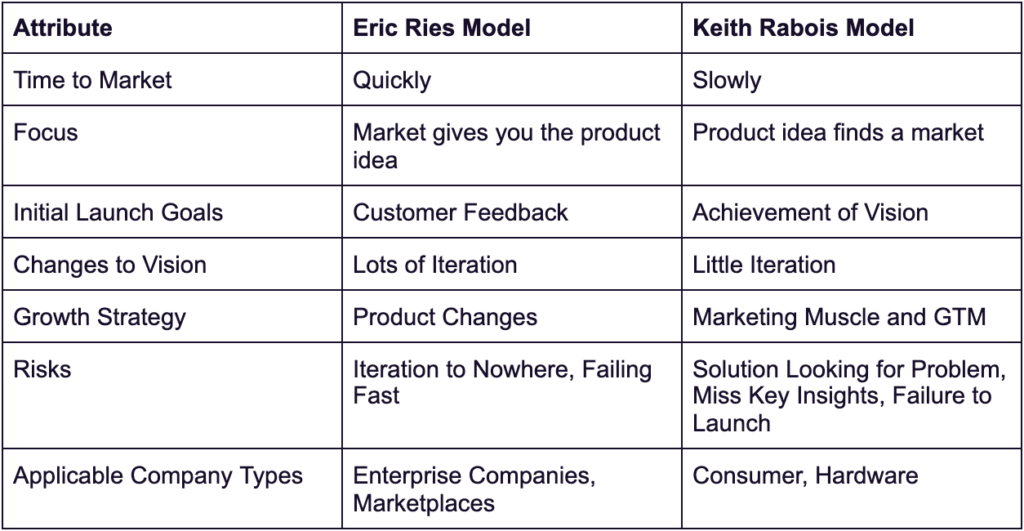

My previous post on product/market fit mentioned the Ries vs. Rabois model on finding product/market fit, which you can think of as testing vs. vision. While both concepts have value, attempts at finding product/market fit with network effects businesses tend to reward more of the Rabois model, or else the testing you do will be inconclusive on the reasons why something isn’t working between the core value prop vs. the size of the network. Finding product/market fit for these types of businesses is much harder, but can be much more rewarding in terms of scale if successful.

Currently listening to my Hipster House / Lofi House playlist.