On The Spectrum: Thoughts on Zuckerberg, Tradeoffs, and Cultural Values

Most companies don't know how to set their cultural values. I explain that values are about making a choice, and seeing if the choice you made is actually being made on a day to day basis.

Many founders spend a lot of time trying to codify their culture and get culture right for their company. Yet many companies end up with serious cultural issues as they scale. Frequently, this is due to a forest for the trees approach to culture. Companies think they maybe they can hide lack of alignment and political strife with pool tables and company offsites, and are surprised when they still have employee attrition problems. Most founders get past that and try to codify strong cultural values that instill how they want to work to get things done at their company. But these values are frequently some mythical view of how things could work vs. how things actually do work. The average response of an employee to a complete set of these values is slightly better than an eye roll. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen goals like “Be aggressive” at a company, but everyone is the opposite, or something is set as a cultural value that is just a thing all people should do anyway, like “Think like a founder,” when the problem is people don’t know how.

Lots of ways to define company culture, but "culture is what happens when the boss isn't around" is still my favorite.

— Siqi Chen (@blader) November 19, 2014

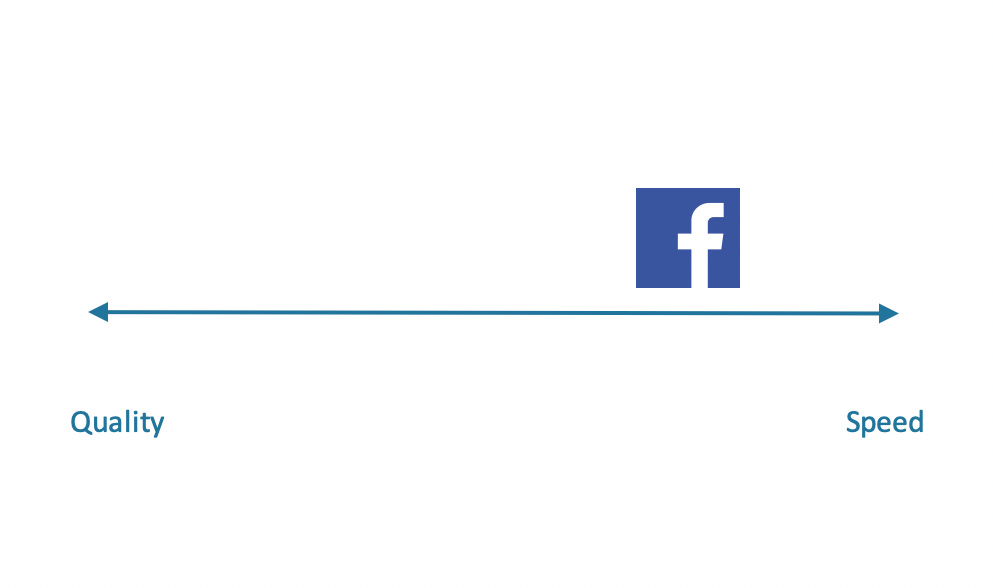

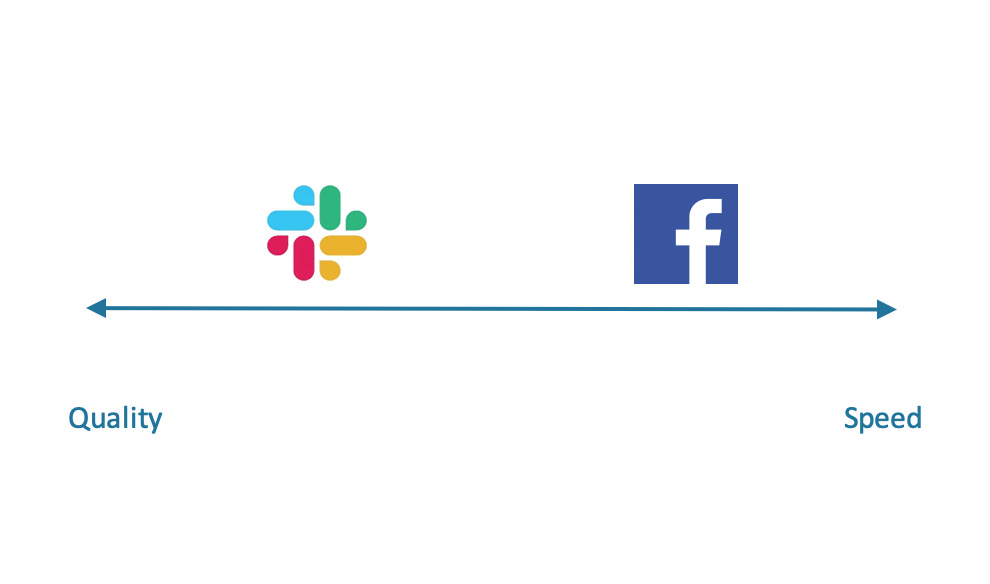

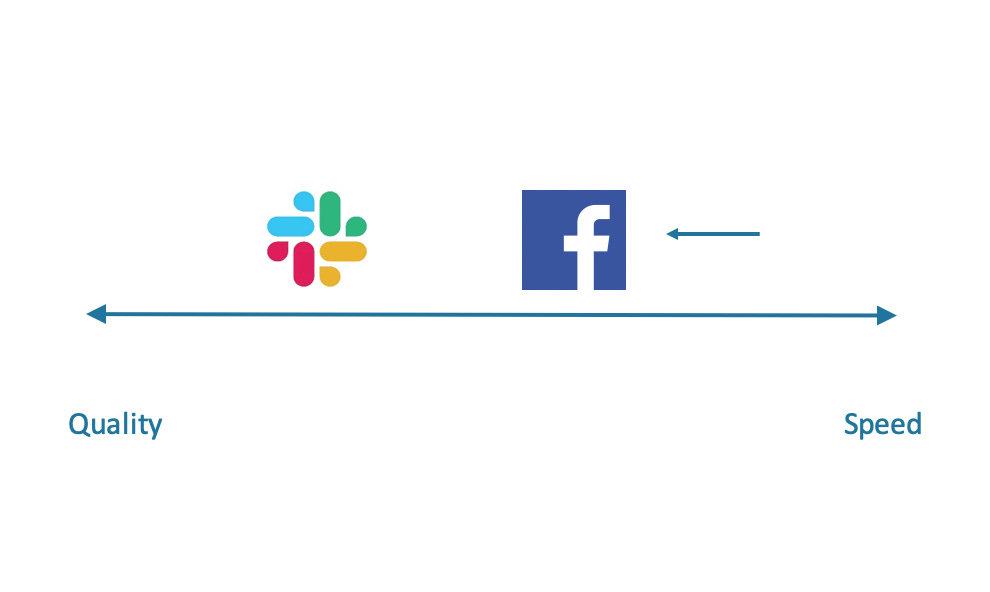

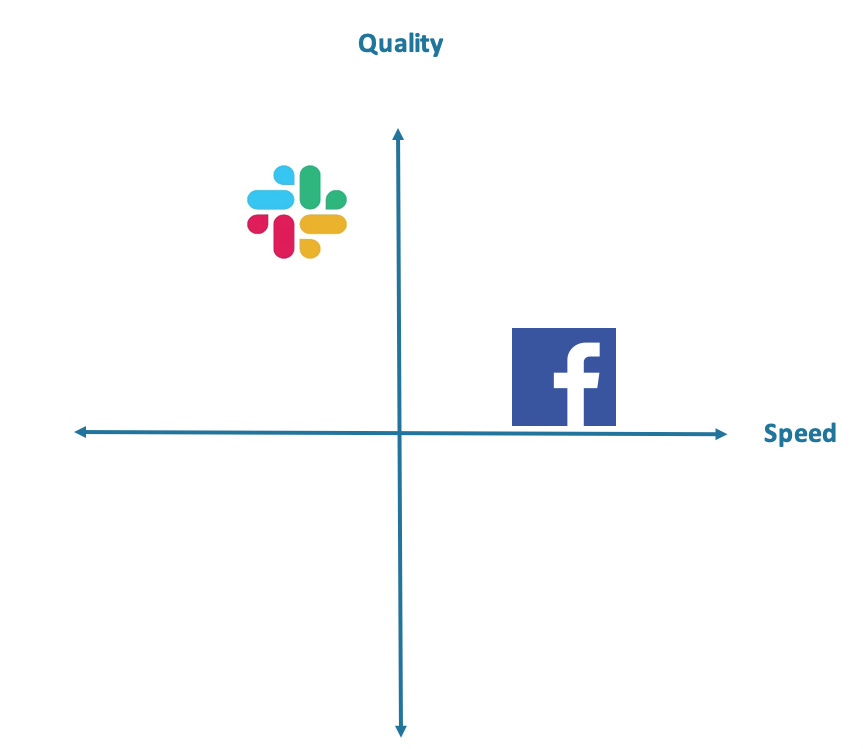

Mark Zuckerberg has taken a lot of flack for some of his management at Facebook over the years, but I believe it was he who most clearly defined what a cultural value is and isn’t. Company values (among many other parts of building a company) are about asking, “What are you willing to give up?”. When Facebook chose “Move fast and break things” as a cultural value, they put speed and quality on a spectrum, and said they biased toward speed.

Compare that to Slack. On Slack’s website, they list a few cultural values, including: Craftsmanship, Courtesy, and Solidarity. They too are picking a place on the speed vs. quality spectrum, and I bet with those words it’s a lot closer to quality.

Neither of these is wrong in isolation. It depends on your market, your competition, your value prop, etc. In all cases, it’s important to pick where you are though. More recently, Facebook switched its core value to “Move fast with stable infrastructure.” It doesn’t have quite the same ring to it, but it’s a signal to the company that at their scale, they need to prioritize quality a little more.

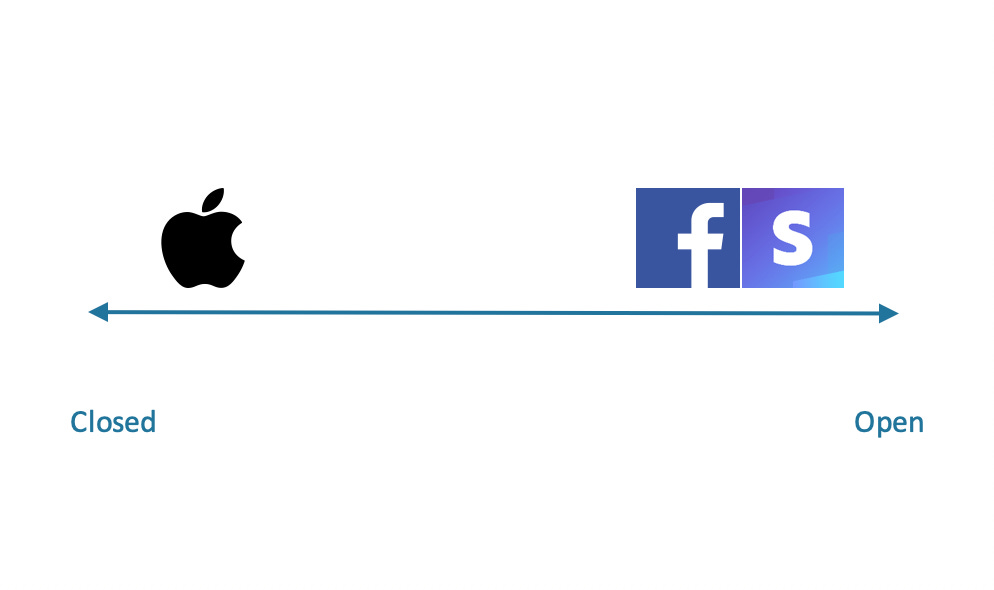

There are other spectrums to consider when managing culture for a company. One is around openness. Again, here, Facebook has a value that mentions specifically how they think about it, with “Be open,” where they say “We work hard to make sure everyone at Facebook has access to as much information as possible about every part of the company so they can make the best decisions and have the greatest impact.” Stripe is another company famous for swinging to the open side of the spectrum. Most of the email at Stripe is available for anyone at the company to read, for example. Compare this to Apple, where most projects are handled in secret, and information is given on a need-to-know basis.

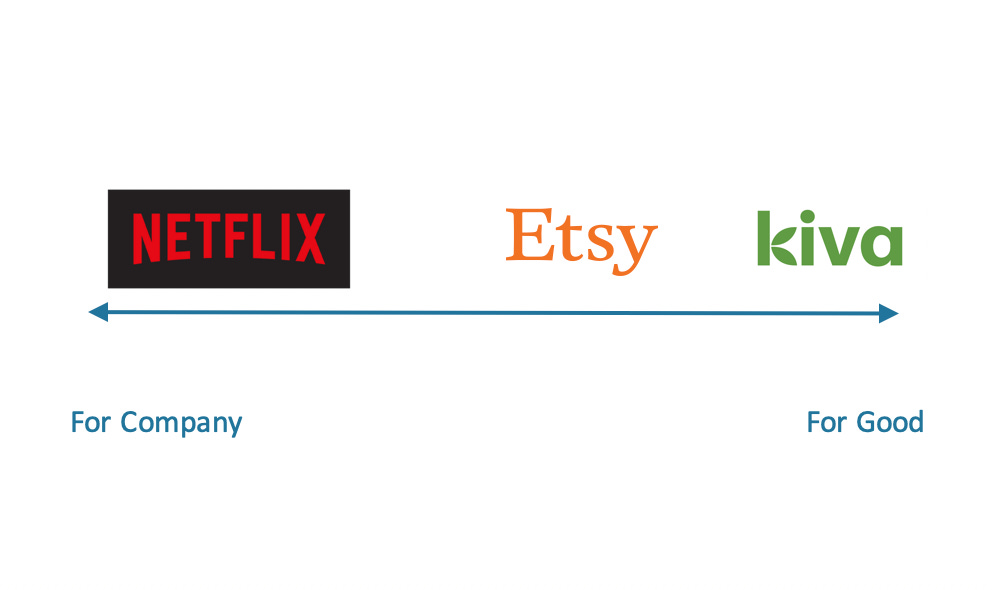

Another classic tradeoff is good for company vs. good for world. Take a company like Netflix that ruthlessly measures performance, and focuses on time spent on the platform. It very much biases towards good for company on this spectrum. But take a company like Etsy or Warby Parker that is certified as a B corporation. That’s an explicit signal that they are trading off some company performance for social responsibility. Then there’s of course companies like Kiva, which are non-profits.

There are others like data vs. intuition, but you get the point. Plotting your company values on a spectrum is important to setting values that actually matter and driving decision-making at scale. Most that make "company value" level should be ones where you are taking a more extreme position. What’s really interesting is if you spend time working at companies is many companies don’t appear to be on the spectrum for some of these company company trade-offs. Now, for direct opposites like open and closed, that’s impossible, except for being inconsistent. But some companies are neither fast, nor do they deliver quality products. Some companies are not providing great financial returns or social returns. In this case, our spectrum becomes a 2x2.

For illustration purposes only. I do not purport to know where Slack and Facebook actually sit on this 2x2. As in all 2x2’s, it’s the worst to be in the bottom left. If you find this to be the case, the first step is to get on the spectrum. Make a decision about where you want to be, and work to get there. Then, once you’ve landed on the spectrum, you can try to optimize toward getting to the top right of the 2x2. Even though Facebook changed its value, I bet it’s still faster at building and higher quality than a lot of other companies. The same can be said for Slack. Except for Slack Threads. They definitely drifted into the bottom left on that one. I... really hate Slack Threads. Whether you update your company values to reflect these spectrums is not the point of this post. The point is to be intentional about the tradeoffs you’re making, and revisit them over time to make sure they still make sense, like Zuckerberg did. You may find you’re not making a tradeoff at all; you’re just performing poorly on both axes, or you may find that the value you picked five years ago no longer matches the needs of your company. Thanks to Brian Balfour for reading through an early draft of this and providing his feedback. Currently listening to Flamagra by Flying Lotus.