Feature/Product Fit

Most teams do not have a great process for figuring out how to add new features to improve the core product. I walk through my framework on how to make sure your feature adds value, and how to measure it.

Through various methods, Silicon Valley has drilled into the minds of entrepreneurs the concept of product/market fit. Marc Andreessen says it’s the only thing that matters, and Brian Balfour has an amazing series of posts that talk about how to find it. But what happens after you find product/market fit? Do you stop working on product? I think most people would argue definitely not. Post-product/market fit, companies have to balance work creating new product value, improving on the current product value, and growing the number of people who experience the current value of the product. While I have written a lot about how to do that third step, and even wrote a post about thinking about new product value, I haven’t written much about how do that second part.

What is Feature/Product Fit? Every product team tries to make their core product better over time. But sadly, at most companies, the process for this is launching new features and hoping or assuming they are useful to your existing customers. Companies don’t have a great rubric for understanding if that feature is actually valuable for the existing product. This process should be similar to finding product/market fit, but there are some differences. I call this process feature/product fit, and I’ll explain how to find it.

In product/market fit, there are three major components you are searching for. I have written about my process for product/market fit, and Brian Balfour, Shaun Clowes, and I have built an entire course about the retention component. To give a quick recap from my post though, you need:

Retention: A portion of your users building a predictable habit around usage of your product

Monetization: The ability at some point in the future to monetize that usage

Acquisition: The combination of the product’s retention and monetization should create a scalable and profitable acquisition strategy

Feature/Product Fit has a similar process. We’ll call this the Feature/Product Fit Checklist:

The feature has to retain users for that specific feature

The feature has to have a scalable way to drive its own adoption

Feature/Product Fit has a third requirement that is a bit different: the feature has to improve retention, engagement, and/or monetization for the core product.

This last part can be a bit confusing for product teams to understand. Not only do the products they are building need to be used regularly and attract their own usage to be successful, they also need to make the whole of the product experience better. This is very difficult, which is why most feature launches inside companies are failures. What happens when a feature has retention and adoption, but does not increase retention, engagement, or monetization for the company? This means it is cannibalizing another part of the product. This might be okay. As long as those three components do not decrease, shipping the feature might be the right decision. The most famous example of this is Netflix introducing streaming so early in that technology’s lifecycle, which cannibalized the DVD by mail business, but was more strategic for them long term.

What is a Feature Team’s Job? You would be surprised how many core product features are shipped when the new feature decreases one of those three areas. How does this happen? It’s very simple. The team working on the feature is motivated by feature usage instead of product usage, so they force everyone to try it. This makes the product experience more complicated and distracts from some of the core product areas that have feature/product fit.

If you own a feature (and I'm not saying it's the right structure for teams to own features), your job is not to get people to use that feature. Your job is to find out if that feature has feature/product fit. You do this by checking the three components listed above related to feature retention, feature adoption, and core product retention, engagement and monetization. During this process, you also need to determine for which users the feature has feature/product fit (reminder: it’s almost never new users). Some features should only target a small percentage of users e.g. businesses on Facebook or content creators on Pinterest. Then and only then does your job shift to owning usage of that feature. And in many teams, it’s still not your job. The feature then becomes a tool that can be leveraged by the growth team to increase overall product retention, engagement, and monetization.

Mistakes Feature Teams make searching for feature/product fit Feature teams commonly make mistakes that dissatisfy the third component of feature/product fit at the very beginning of their testing.

Mistake #1: Email your entire user base about your new feature Your users do not care about your features. They care about the value that you provide to them. You have not proven you provide value with the feature when you email them early on. Feature emails in my career always perform worse than core product emails. This inferior performance affects the value of the email channel for the entire product, which can decrease overall product retention.

Mistake #2: Put a banner at the top of the product for all users introducing the new feature New features usually target specific types of users, and are therefore not relevant to all users. They are especially irrelevant to new users who are trying to learn the basics about the core product. These banners distract from them, decreasing activation rates. It’s like asking your users if they’re interested in the Boston Marathon when they don’t know how to crawl yet.

Mistake #3: Launch with a lot of press about the new feature PR for your feature feels great, but it won’t help you find feature/product fit. PR can be a great tool to reach users after you have tested feature/product fit though. It should not happen before you have done experiments that prove feature/product fit. And it will not fix a feature that doesn’t have feature/product fit.

Many features won’t find feature/product fit Many of the features product teams work on will not find feature/product fit. When this happens, the features need to be deleted. Also, some older features will fall out of feature/product fit. If they cannot be redeemed, they also need to be deleted. If you didn’t measure feature/product fit for older features, go back and do so. If they don’t have it, delete them. Some of our most valuable work at Pinterest was deleting features and code. A couple examples:

The Like button (RIP 2016): People did not know how to use this vs. the Save button, leading to confusion and clutter in the product

Place Pins (RIP 2015): Pinterest tried to create a special Pin type and board for Pins that were real places. As we iterated on this feature, the UI drifted further and further away from core Pinterest Pins and boards, and never delivered Pinner value

Pinner/Board Attribution in the Grid (RIP 2016): Attributing Pins to users and their boards made less sense as the product pivoted from a social network to an interest network, and cluttered the UI and prevented us from showing more content on the screen at the same time

How do I help my feature find Feature/Product Fit? All features should be launched as experiments that can test for feature/product fit. During this experiment, you want to expose the new feature to just enough people to determine if it can start passing your feature/product fit checklist. For smaller companies, this may mean testing with your entire audience. For a company like Pinterest, this might start with only 1% of users. The audience for these experiments is usually your current user base, but can be done through paid acquisition if you are testing features for a different type of user.

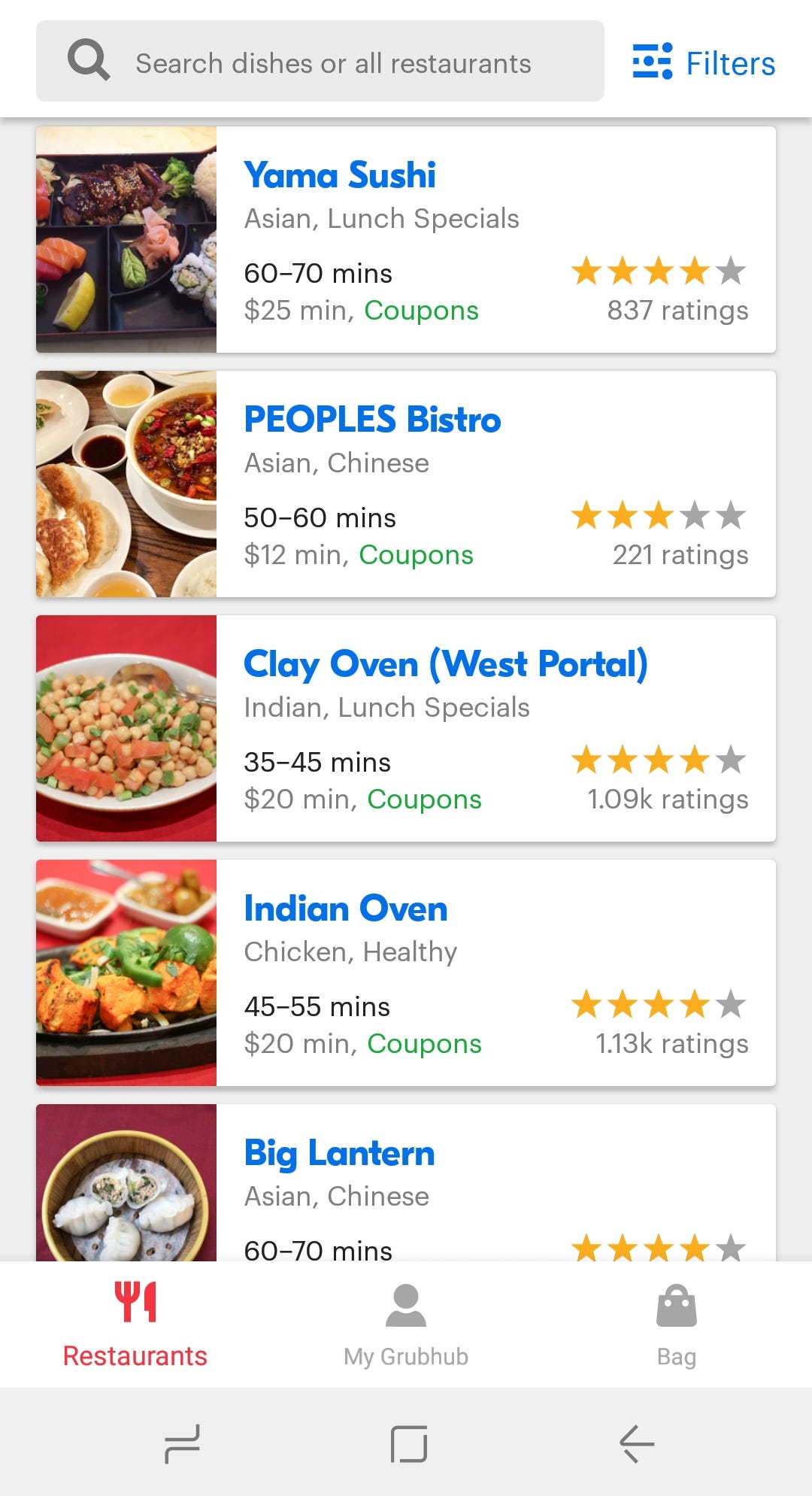

I’ll give you a few tactics that have helped the companies I’ve worked on find feature/product fit over the years. Most good product development starts with a combination of data analysis and user research. User research should be involved at the right times to add the most impact, prevent confirmation bias, and determine what components users are struggling to see the value of. For example, when we launched the Grubhub mobile app, we saw in the data when people used the current location feature, their conversation rate was lower than people who typed in their address. This turned out to be an accuracy problem, so we turned that component until off until we were able to improve its accuracy.

In research, we saw people were having trouble figuring out which restaurants to click on in search results. On the web, they might open up multiple tabs to solve this problem, but this was not possible in the app. So, we determined what information would help them decide which restaurants were right for them, and started adding that information into the search results page. That included cuisine, estimated delivery time, minimum, star rating, number of ratings, On the surface, the page now feels cluttered, but this improved conversion rates and retention.

Since Grubhub is a transactional product, we were able to leverage incentives as a strategy to help find feature/product fit. Our early data showed that people who started to use the mobile app had double the lifetime value of web users. So, we offered $10 off everyone’s first mobile order. This transitioned web users to mobile for the first time and acquired many people on mobile first. The strategy was very successful, and the lifetime value improvements remained the same despite the incentive.

Grubhub also uses people to help find feature/product fit. Since mobile apps were new at the time (and we were the first food delivery app), we monitored any issues on social media, and had our customer service team intervene immediately.

Not all complaints are this entertaining.

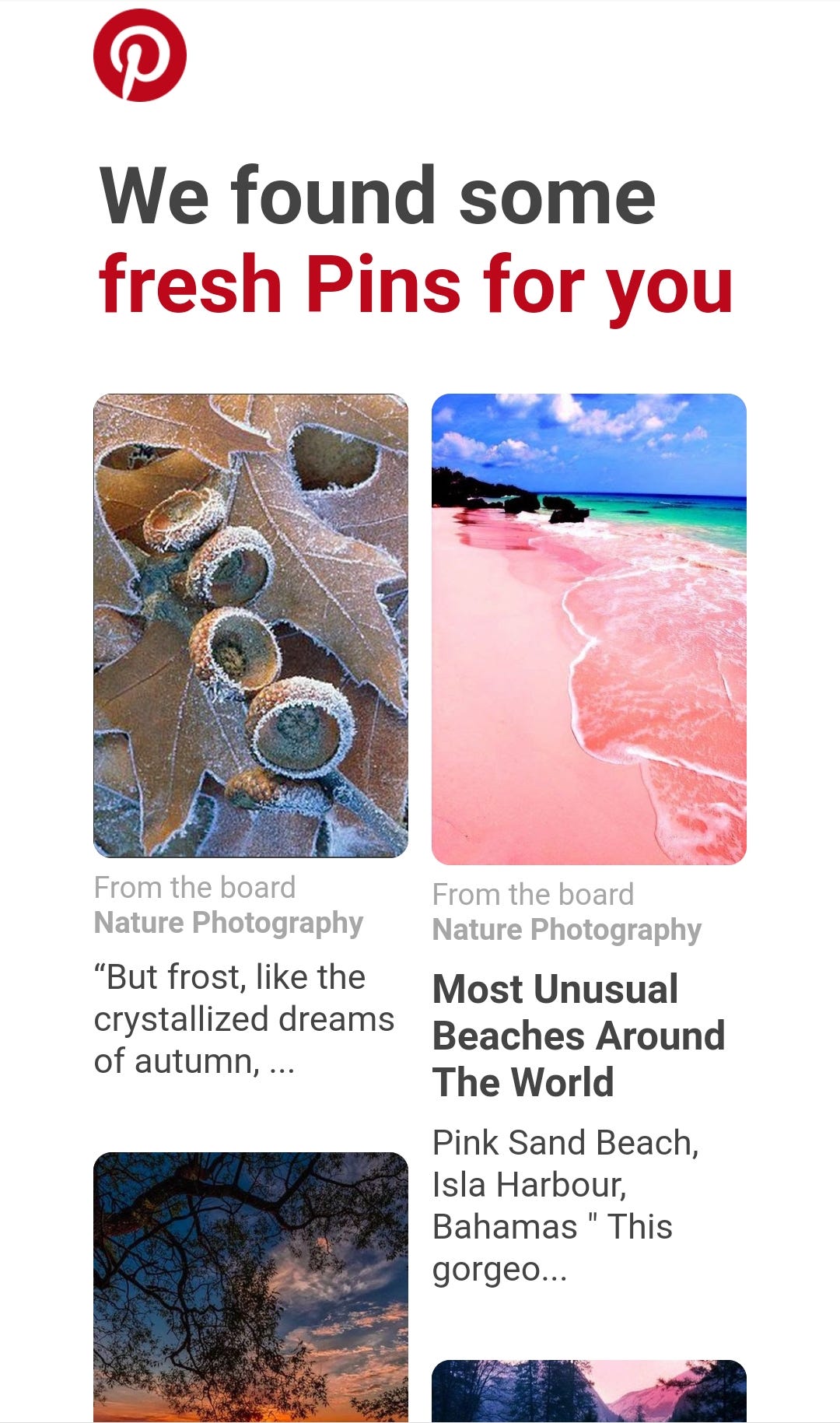

At Pinterest, we launched Related Pins in 2013. For Pinterest, we did not have a revenue model at the time, so tactics around incentives and people do not make as much sense. One thing we did instead was use notifications to drive feature/product fit. Once this algorithm was developed, after you Pinned something, we could now email you more Pins you might like that are related to that Pin. These emails were very successful.

Pinterest also used the product to drive feature/product fit. We launched the algorithm results underneath the Pin page to start, and interaction when people scrolled was great. But many people didn’t scroll below the Pin. So, we tried moving them to the right of the Pin, which increased engagement, and we started inserting related Pins of items you saved into the core home feed as well, which increased engagement.

The Feature/Product Fit Checklist When helping a product find feature/product fit, you should run through this checklist to help your feature succeed:

What is the data telling me about usage of the feature?

What are users telling me about the feature?

How can I use the core product to help drive adoption of the feature?

How can I use notifications to help drive adoption of the feature?

How can I use incentives to help drive adoption of the feature?

How can I use people to help drive adoption of the feature?

When confirming feature/product fit, you need to ask:

Is the feature showing retention?

What type of user(s) is retaining usage of the feature?

How do I limit exposure to only those users?

What is the scalable adoption strategy for the feature for those users?

How is this feature driving retention, engagement, or monetization for the overall product?

Every company wants to improve its product over time. You need to start measuring if the features you're building actually do that. You also need to measure if existing features are adding value, and if not, start deleting them. Asking these questions when you build new features and measure old features will make sure you are on the path to having features that find feature/product fit and add value to users and your business.

Thanks to Omar Seyal and Brian Balfour for reading early drafts of this.

Currently listening to Breaking by Evy Jane.